Here in the UK we don't save nearly enough money. According to the latest statistics, many of us are living hand to mouth, going from pay cheque to pay cheque and failing to put money aside, be it for pensions, rainy days or with a particular purpose in mind, like a deposit for a house.

On the other hand we have become extremely good at spending money. These days we want more and we want it right now, and due to the growth in access to credit cards and the ease and speed of online shopping, we can usually get what we want right now too. At the same time there are more and more demands on our money: we lead more active lives and we are living longer to boot, so not only will we need more money to support us in retirement, but there are also more immediate concerns, like having to support our children for much longer, often well into their adult lives. The rising cost of living has also made it harder for us to set money aside, since after we've paid essential bills, and with our utilities outlay now encompassing a raft of technological necessities (mobile phone, broadband and cable contracts etc) as well as the basics, there's not much left.[1]

In this article, which is part two of our three-part series focusing on personal financial management, we look at a number of individual behavioural traits together with aspects of our day to day lives to better understand why we are bad at saving money. We then examine four innovative applications of behavioural science which are helping people to save more.

...So just how bad are we at saving money?

The facts paint a fairly dismal picture:

- The proportion of our income that we save peaked decades ago in 1979, when we saved 14% of our income on average. Since then rates have fallen dramatically, dropping to as low as 2% in 2008. Post financial crisis, rates have hovered around 7%, but dropped again in 2013 to just 5%. So a household with a fairly typical monthly income of £1500 ring fences a mere £75 of that for the future.[2]

- A survey conducted in 2013 by HSBC found that one in three households in the UK had less than £250 of savings to fall back on should financial emergencies arise, and one in four had no savings at all. Whilst to some extent the almost zero interest rates we have been experiencing in the UK mean that cash in savings products achieves a very low return, this doesn't negate the need for some sort of easily accessible buffer for unexpected expenses and difficult times.[3]

- The US has also seen relatively low savings rates; household savings have averaged 5% over the past 6 years and a 2012 study found that 55% of American households live pay check to pay check, spending all that they earned or more and 60% of those surveyed had no ‘rainy day fund’ with insufficient emergency savings to cover expenses for three months.[4]

Barriers to saving – why it’s not that easy

The increased ease of spending

Behavioural science experts often point to contextual changes to explain our behaviour. Explanations for our failure to save can also be contextualised. Our day-to-day environment has made us more vulnerable and prone to spending.

It has become increasingly easy for us to spend: credit cards and contactless payment cards have paved the way and online spending is perilously effortless, with ‘one-click purchases’ and offers to save card information for future purchases. All that slick spending activity can easily leave us with little leftover to save. A significant proportion of people now pay for almost all purchases using a debit or credit card.

Stressed out 21st century lifestyles mean we are also more vulnerable to spending. Research by Roy Baumeister, Professor of Psychology at Florida State University, shows that individual self-control – often called ‘the moral muscle’ - is a finite resource, and just like any other muscle it can get tired and give out. If we've exhausted it during a long day which started with going to the gym when we'd rather have stayed in bed, and also included moments of turning down second helpings when we'd have killed for a piece of cake, or determining to go through that pile of papers on our desk and take action when it's positively the last thing we want to do, at some point we will probably get tired and give in to something, because resisting temptation can take it out of us. And if work’s been tough, or we're stressed, then the chances are we'll spend more than we should shopping online when we get home.

Only some of us are wired to save (Nature) 'It’s not my fault it's in my DNA'

Despite the changing context described above, we all know people, even those who have relatively little income, for whom saving seems second nature. They squirrel money away, putting it aside for far into the future. Maybe you're one of those people yourself? But why is it that some of us find it easy to save and others find that money burns a hole in their pocket until it is spent?

Neuroscientists explain this by pointing out how we are all wired differently. Some of us are more prone to certain cognitive biases such as discounting the future and the ‘power of now, or optimism bias than others. Let's examine some of these variations:

-

Wired with better self-control

Certain genetic dispositions mean that some of us are simply born with better self-control and a natural instinct about how to steer ourselves away from temptation. Children who are better at delaying gratification and using self-control have been found to go on to do better in life as adults. Walter Mischel’s marshmallow experiment showed that children who grasped the notion of delayed gratification and were able to hold out for two marshmallows rather than giving in and eating the single marshmallow in front of them were more likely to succeed later in life. They got better exam results, performed well at university, were less likely to be obese or have drug problems – and were more capable of managing and saving their money. Mischel (seen here) says this is because these children understood how to distract themselves from temptation:

'If you can deal with hot emotions, then you can study for the S.A.T. instead of watching television… and you can save more money for retirement. It’s not just about marshmallows.'[5]

Research into what causes variations in self-control, self-regulation and impulsivity from a young age has found that genetic variations can account for around half of the differences in low self-control. Estimates vary from as low as 40% to as high as 64%, but importantly, these variances are stable over time.[6]

-

Wired to learn from experience

Insights from neuroscience show that people have different variants of the COMT gene – a gene which has an important influence on how we learn from experience, which certainly includes financial behaviour and experience in dealing with money. Specifically, one variant of this gene increases the amount of the hormone and neurotransmitter dopamine in the pre-frontal cortex in our brain – the area of our brain known for rational, logical thinking and weighing up decisions. Neuroscientists have shown that a moderate release of dopamine is important for learning from new outcomes because it helps working memory and our executive control. It’s thought around 1 in 4 people have this COMT variant and they tend to make better financial decisions and excel at long term planning because they have learned from experience how to manage their money optimally.[7]

'If you are lucky to be born with this variant of the gene, then the particular portion of your brain that’s associated with weighing ‘costs and benefits’ winds up receiving more dopamine and works better.' says Hersh Shefrin, a behavioural economist at Santa Clara University who has studied these differences amongst us.[8]

-

Wired to feel the pain of spending money more acutely

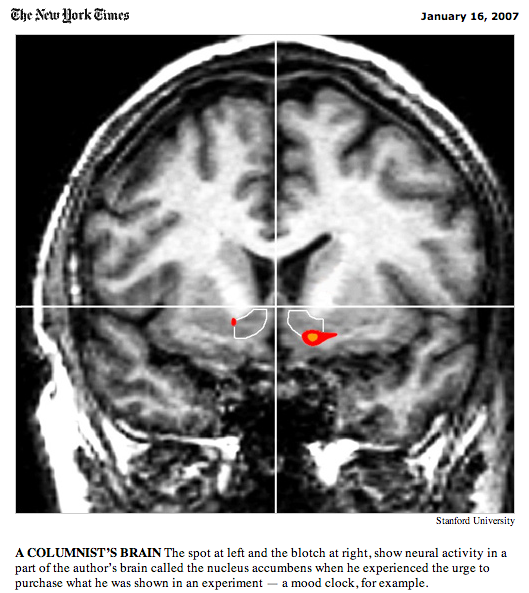

Neuroscientists have also found that some people register paying for purchases more painfully than others, meaning that they may have more money to save, simply because they haven’t been able to take the agony of spending it. They found there to be actual physiological effects in the brain showing differences in responses to price which ultimately affect our behaviour. MRI scans by Stanford psychologist Brian Knutson and colleagues discovered that the insula, the area of the brain known to register many different types of pain – from repulsive odours, to unfair games, social exclusion and loss – also registers activity when we see a price - probably because we know we might have to ‘lose’ or hand over our money if we go ahead and buy something.

Knutson and his colleagues gave 26 adults $20 which they were free to spend on a number of different items. They viewed pictures of the different items and their prices whilst placed in an fMRI scanner. Participants’ insulas activated whenever they saw prices that they considered too high for the associated product and, where this happened, they were consequently less likely to purchase that product.[9]

Knutson also tested John Tierney, the New York Times columnist in this way and results showed that he was more of a spendthrift than the average study participant. He chose to buy 50% of the items on offer, compared to most people who purchased only 30% of the items.[10][L1]

4. Wired by different motivations to save

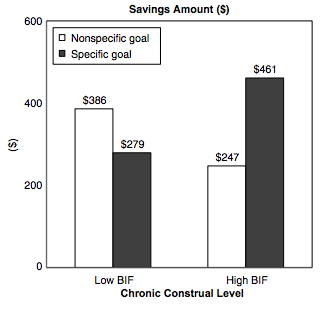

Behavioural scientists Amar Cheema and Gulden Ulkumen have found that how much people save depends to some extent on how they motivate themselves in all sorts of different behaviours. While some people are motivated by keeping in mind how they are doing something; others are more motivated by why.[11] For example, when motivating themselves to make a list, some people might think only about how they will achieve that: ‘I will make a list by writing things down’ whilst others think of the rationale behind the activity: ‘It will help to get me organised’.

When Cheema and Ulkumen asked 99 students to define and save for an upcoming occasion, they found that those who saved the most – often more than they needed – were those who were asked to set a specific savings target to aim for and who tended to think about why they were saving the money, rather than how.

The target focused group saved $461 on average whereas those who had not defined an exact amount saved only $247 on average.

Conversely, defining a target amount to save for did not help the students who were more motivated by thinking about how they would achieve their goal. They saved only $279 on average compared to the average savings of $386 among those who had defined no specific goal.[12]

5. Wired to be optimistic

Other dispositions which may affect our savings behaviour are related to our inbuilt degree of optimism and confidence about the future – some of the more optimistic among us might believe that one day we will win the lottery, create a successful business or come by a large inheritance and rely on these imagined windfalls to decide that there is no reason to save in the meantime. Others who are naturally more pessimistic about the future anxiously put money away to insure against difficult times and financial shortages.

Genetic influences such as those described above have been found to explain around 35% of savings behaviour. In a study of over 1,500 identical and fraternal twins and their parents using Sweden’s Twin Registry, researchers Henrik Cronqvist and Stephan Siegel found that savings behaviour was more correlated among identical twins than fraternal.[13] This effect is present over a lifetime and does not lessen as people age. Behavioural geneticists are now researching more deeply into the genes that might be behind the variations in our behaviour.[14]

But nurture can fight against nature

For those of us not blessed with any of the traits which determine a more successful approach to saving, there's no need to resign ourselves to squandering our money in the course of our lives. We can actually train ourselves to become better at regulating our behaviour. Behavioural geneticists have shown that our willpower and self-control can be influenced not only by our genes (nature) but also by our upbringing and ability to learn about our environment (nurture) and self-regulate in response.[15] Even though we may have been born with a disposition to enjoy things now rather than later, we can work on our willpower capacity and improve our self-control over time. There are commitment devices and automatic defaults to help here. Typical money related ones are going shopping without any credit cards, or committing ourselves to spending a finite amount of cash, or setting up an automatic direct debit to save into our pensions and savings accounts to prevent us from blowing our money on pay day.

And there are other kinds of interventions leveraging behavioural economics which can help us to make better decisions and behave more responsibly with our money. Here, at last, are four ways in which behavioural insights can be used to help us to save more and more successfully:

1. The power of mental accounting: earmarking and partitioning our savings

One insight from behavioural science has shown how simply partitioning off savings from our everyday spending money has a significant impact on how much we save. Partitioning is a form of mental accounting, a concept first identified by behavioural economist Richard Thaler, by which we categorise, compartmentalise and treat money differently depending on where it comes from, where it is kept, or how it is to be spent. So we are more likely to be reluctant to spend money we have already mentally allocated for savings.

Dilip Soman and Amar Cheema looked at ways in which low-income households in India with very little spare cash, could be nudged into saving towards important goals such as saving money towards their children’s upbringing, using a form of mental accounting. These households were typically earning just 670 rupees per week (£6.60 or $11.20) so there were very low savings rates. Most households only managed to put aside 5 rupees each week - a pitiful savings rate of 0.75%.

Yet working with a local financial planner who showed that it was possible for them to set aside as much as 40 rupees each week – a savings rate of 6% - reaped success. How? Simply by setting aside the allotted rupees in a designated envelope each week. Partitioning savings in this way nearly doubled the savings rate; savings dramatically increased over the 14 weeks of the study, with average savings of 377 rupees (27 rupees per week or a savings rate of 4%). In contrast, households who did not use envelopes only saved 230 rupees (16 rupees per week or a 2.5% savings rate).

Mental accounting plus – making it work even harder

The success of this intervention was also due to two further factors.

-

Committing to a goal

It’s likely that giving households a defined savings goal helped. Asking individuals to identify a savings goal, for example, a deposit for a house or replacing their car and define a specific amount which they need to save to achieve this goal has been shown to be successful in academic literature as well as in practice. Amar Cheema and Gulden Ulkumen found that defining a set amount to save and keeping in mind the reason why (earmarking the money in other words) makes it more likely we will achieve our goal. This may be because people generally feel more committed to a goal when it is specific; because of the lack of ambiguity, success or failure is easier to define so it’s harder to invent creative excuses about why we didn’t manage to save £1000 for a holiday than when the goal is less defined and less specific.

Encouragingly some people in the UK already save in this way. A 2013 UK NS&I survey found that just over a quarter of Britain’s savers (28%) set specific savings goals, and that those with goals are saving around £150 a month in total, compared to £111 by those saving for no specific reason. The main reasons for saving were for a deposit for a house, home improvements, a holiday or special occasion with some also saving for financial emergencies.[16]

-

Making a savings goal salient

Soman and Cheema found that savings among the Indian households in their study rose higher still if they asked these households to stick a picture of their children on the envelope into which they were putting their weekly savings. By the end of the 15 weeks, households using envelopes with photos on had saved 450 rupees on average (32 rupees each week or a 4.8% savings rate). Households not only saved more, but they were also less likely to raid their savings when tempted to spend instead of save.

Why did this intervention work? Behavioural science tells us that images make things more salient and vivid. Not only do we have an affective, emotional reaction to seeing a photo, but it also helps to keep the goal front of mind so having the photo of their children on the envelope provided a constant, vivid reminder of why they were saving.[17]

People often discover this technique themselves. An American woman who was struggling to save described on a money management website how she thought of the idea to start to save her money for different purposes into envelopes with photos. She said:

“While my husband would put money away into general savings, without any goal in mind, I knew that this just didn’t work for me. I couldn’t get amped about putting money away for some non-specific purpose.

That’s when my envelope idea kicked in. I figured out that, rather than saving for obscure purposes, I needed to root my savings to specific goals that I could visualise. I started by making different envelopes for different dreams – Emergency Fund, Waterpark, Long weekend Away with Family, Start Our Own Business – and drew pictures on each one. Having to actually visualise what those goals looked like made me connect with them – and really inspired me! Since then, we’ve saved nearly $4,000. I’m now on my way to having all of my pre-marriage debts cleared, and we’re putting money away like it’s going out of style! Having the vision makes it so much easier.” Shannon on the LearnVest website[18]

That’s when my envelope idea kicked in. I figured out that, rather than saving for obscure purposes, I needed to root my savings to specific goals that I could visualise. I started by making different envelopes for different dreams – Emergency Fund, Waterpark, Long weekend Away with Family, Start Our Own Business – and drew pictures on each one. Having to actually visualise what those goals looked like made me connect with them – and really inspired me! Since then, we’ve saved nearly $4,000. I’m now on my way to having all of my pre-marriage debts cleared, and we’re putting money away like it’s going out of style! Having the vision makes it so much easier.” Shannon on the LearnVest website[18]

It’s clear from Shannon’s account that she is someone who desperately needs to keep in mind why she’s saving whereas her husband was driven by different motivations.

What can we learn from this? Reflect on what motivates you to save. Are you more motivated by why you are saving or how you are saving? Would it help you to set a specific monetary savings target or would you achieve more with a more general goal and an innovative method of saving, perhaps through a new app or novel strategy? Also, do financial services providers need to build flexibility into the design of their savings products to take into account the different ways in which people are motivated?

Real life applications of salient, partitioned goal saving

It’s exciting to see that some financial service providers are already innovating in this area and leveraging some of the insights from behavioural science that we have explored above to create highly effective savings tools. Below we illustrate how RBS/NatWest, Saffron Building Society in the UK and Simple Bank in the US have been applying behavioural science:

- RBS/NatWest have developed an award-winning Savings Goal tool which allows customers to define the goal they are saving towards and the target date. It calculates a savings plan and tracks their progress towards that goal. Only one savings goal is permitted per savings account, making sure that funds stay separate.[19] The bank also motivates and rewards people through constant updates and encouraging messages.

By the end of 2013, 200,000 people were using the product. These customers were observed to be saving £189 more each month than people using regular savings accounts with no explicit goals. Customers are also remarkably successful in achieving their goals – 99% of wedding goals set in the first half of 2013 were attained, both in terms of target date and amount, 80% of rainy day and house deposit goals were also realised. Overall, the account had a 70% success rate in the first half of 2013.[20] Customer responses to an Ipsos MORI survey of users helps to illustrate the reasons for success:

- 'It’s only a small thing that I saw for saving for my last holiday but it made me really proud and goals are now an essential part of my life.'[21]

- 'I found it encouraging that I’m on target to achieve my goal much quicker than average. It helps motivate me to keep saving as much as possible.'

- 'It makes me more aware of my savings and what I’m saving for. It also encourages me to stick with my goal.'

-

Saffron Building Society has developed a similar goal saver account called ‘Plan, Save, Get your Goal’, helping customers to make a defined plan to save – what for, when for and how. Pre-defined common goals also include an image, helping to make a goal more salient (here's the image for their

emergency savings goals) and these can also be personalised by uploading your own image, making them even more salient. For common goals such as saving for a wedding or a new car, they have designed separate websites with three very clear steps, one of which is the reward of achieving the goal eg ‘Plan, Save, Get Married!’ helping to make the ‘why’ behind our saving very salient and front of mind.[22]

emergency savings goals) and these can also be personalised by uploading your own image, making them even more salient. For common goals such as saving for a wedding or a new car, they have designed separate websites with three very clear steps, one of which is the reward of achieving the goal eg ‘Plan, Save, Get Married!’ helping to make the ‘why’ behind our saving very salient and front of mind.[22]

Both RBS/NatWest and Saffron’s savings accounts gained awards in the Fairbanking Foundation ratings last year. The Fairbanking Foundation is a charity which rates core banking products for the extent to which they can help customers improve their financial well being. RBS/NatWest achieved the first ever five star accreditation in Autumn 2013 while Saffron achieved a three star rating.[23]

- Similarly, US bank Simple allows customers to create savings goals within their current account. All they need to tell their account is how much they need to save and when for. Simple’s technology will then automatically calculate how much they need to save each day to get there and automatically ‘transfer’ or partition the money off from their main account. When the customer has reached their goal, they can simply switch to ‘spend from goal’ – virtually raiding the piggy bank.

Simple have quickly seen how innovations such as goal saving have helped their customers toward positive behaviour changes. Their analysis has found that customers who save and budget with goals save twice as much as customers who don't.

Like RBS/NatWest and Saffron, Simple Bank’s device works via a number of factors:

- Goal saving leverages commitment bias – we are more likely to achieve a goal when we explicitly state what we’d like to achieve, especially if we do it publicly.

- The technology involved also makes the savings automatic – once the goal saving has been set up customers probably won’t even notice the money being siphoned away and they don’t have to remember or motivate themselves to make regular transfers.

- Simple also helps customers plan more specifically, so rather than a vague goal to ‘save more’ or ‘save for a new fridge’ it forces them to consider how much and by when.Lastly, Simple makes the goals salient. The savings aren’t hidden away, but visible and salient within the account. Progress towards a goal is tracked on a progress bar, helping to motivate savers, especially as they get closer to their goal.

- Lastly, Simple makes the goals salient. The savings aren’t hidden away, but visible and salient within the account. Progress towards a goal is tracked on a progress bar, helping to motivate savers, especially as they get closer to their goal.

2) Building a savings habit with regular triggers and small steps

Starting to save can seem a daunting prospect, especially if you’ve never tried to before or haven't had any success in the past. If we are not in the habit of saving, it can be a struggle. Insights into consumer psychology show that to successfully build a habit, we need a trigger – a regular time or location which automatically brings to mind a particular behaviour, or routine. It can also help, particularly at first, to have a reward – some sort of incentive or motivation to carry out that behaviour.

HelloWallet – a technology-based personal financial management service – have recognised the significance of this. HelloWallet encourages users to develop good financial management habits and tackle problems of inertia and procrastination via a weekly Sunday email. This email contains just one small manageable financial task for users to focus on – perhaps simply setting up a rainy-day/emergency savings fund, and no more. HelloWallet point out that it takes just three minutes to set up and by chunking savings behaviour into smaller steps on a weekly basis, people begin to develop better financial habits and are more likely to meet their goals.

HelloWallet’s research shows that success in these small tasks builds people’s confidence and make them feel more able to tackle their finances.

HelloWallet’s research shows that success in these small tasks builds people’s confidence and make them feel more able to tackle their finances.

The timing of the weekly email may also be key; its regularity may help to keep financial management front of mind and the Sunday slot may also be relevant – away from the demands of work, and when we are likely to be at our most rested with replenished levels of self-control. After conducting a number of trials testing the best day and time to send their emails, HelloWallet found that 5pm on a Sunday evening led to the highest click through rate.[24]

We might do better if we nominated a particular time during the week to tackle our finances. Just as our great grandmothers may well have had a weekly domestic schedule that went something like this:

Wash on Monday

Iron on Tuesday

Mend on Wednesday

Churn on Thursday

Clean on Friday

Bake on Saturday

Rest on Sunday

Perhaps we need to make a habit of devoting an hour of our Sunday afternoon to ‘Manage my money’.

3) Improving saving through use of simple rules of thumb

Deciding how we should spend and allocate our money can be difficult and time consuming. Research shows that financial literacy and prowess among the younger generation is often low, so they may be unsure of the best ways to manage their money. We know of one girl who wanted to control her spending so set herself a budget. Sounds sensible? Only the budget she set was a figure pulled out of thin air, not based on her take home income! We may know that we need to save, but how much and how to go about it? How do we draw up a budget? How should we prioritise against paying our mortgage or credit loans?

Following simple rules of thumb and decision-making heuristics or using them as reference points to anchor on can make managing our money and savings far easier, especially for the less financially literate. Top behavioural economist and psychologist, Gerd Gigerenzer believes that heuristics, despite their simplicity, can sometimes lead to optimal decision-making and can in fact be highly accurate. Complex problems do not always require complex solutions and savings for the majority of us are no different. Taking action and building savings up using simple strategies is better than procrastinating and putting off action because we feel we should devote time and energy into improving our financial literacy and devising the perfect set-up first.

Heuristics are easy to keep in mind and remember which makes them more likely to be followed, especially if they come from an authoritative or peer related source. In addition, once set, because of commitment bias and our desire to be consistent in our behaviour, we are less likely to break them. These heuristics (if correct) also help to embed good financial habits in the younger generation, before they get into financial difficulty.

Heuristics are easy to keep in mind and remember which makes them more likely to be followed, especially if they come from an authoritative or peer related source. In addition, once set, because of commitment bias and our desire to be consistent in our behaviour, we are less likely to break them. These heuristics (if correct) also help to embed good financial habits in the younger generation, before they get into financial difficulty.

MoneyFirsts.com and LearnVest[25] - two financial education-focused websites designed to help Millennials better understand their finances and manage their money – use simple heuristics to good effect to help financial management among users of the site. Both websites provide a one-stop-shop for guidance and tips on the key areas of money management.

Their simple heuristics include:

- Emergency savings: 'you should have one month of your income saved up at a minimum—but your goal should be at least six months.'

- The 50/20/30 rule: this helps people to make an effective budget and allocate their money in the most sensible way. They recommend that no more than 50% of take-home pay should go on essentials which cover housing, transport, utilities and groceries. Then 20% should be allocated towards retirement contributions, savings or investments and debt repayments. The last 30% is for personal lifestyle choices such as holidays, phone and internet plans, hobbies, bars or shopping.

- Dealing with a windfall: '…take 10% of your windfall and earmark it for a treat. So if you got a big tax refund, make a dinner reservation. If an inheritance landed in your lap, book a trip. With the 10% rule, you actually allow yourself to celebrate—and you won’t regret spending it all in one place.'

- Pay bills, save, and only then, spend what’s left: Saving is often what is left at the end of the month after all our spending rather than an active decision to save. Rather than saving what is left at the end of the month we should reverse the process and set money aside for different goals at the start of the month: 'Most people spend some money, pay their bills and save what’s left,' says Nancy Butler, a Certified Financial Planner. 'And that’s backwards: You should be saving for your financial goals first, paying your bills and then consider spending the money you have leftover.'[26]

Following these simple rules of thumb may help even the most financially illiterate amongst us to set money aside and gain better control of our money; particularly students and new graduates entering the world of work and suddenly needing to be more financially independent.

We’d love to hear of other useful money rules of thumb being used successfully too. Wouldn’t it be great if rules of thumb like these were more widely known and applied?

4) Reframing savings

The way information is presented to us – or framed - can have significant subconscious effects on our behaviour.

Research has shown how the inclusion of single words can have a noticeable effect on our spending behaviour. Even someone who finds spending painful can be affected by context… something behavioural economics has illustrated time and time again.

A study looking at spending variations across individuals by Scott Rick, Cynthia Cryder and George Loewenstein found that ‘tightwads’ – people who find spending money painful - were more likely to spend if they read the word ‘small’ with an offer.

- When participants in the study were asked if they would be willing to pay a ‘small $5 fee’ to receive a box of DVDs by overnight delivery, tightwads were nearly as likely as spendthrifts to agree (28% vs 37%).

- However, when the word ‘small’ was omitted from the question – so the question was would they be willing to pay ‘a $5 fee’ - tightwads almost all refused to pay (39% spendthrifts vs 8% tightwads).[27]

With these results in mind, there is no reason this sort of reframing couldn’t be applied to saving too, helping to make saving easier for people who struggle in this area. It would be interesting to see this tested and put into action.

Conclusion

So much of our behaviour is affected by context and the context or environment we live in today has made many of us spenders rather than savers. In this second article in our financial series we have seen how some of us are wired to save because nature is on our side. For those not blessed with this wiring we have seen how we can design the context around us to succeed and win our savings battle.

We have seen how insights from the behavioural sciences, with technological advancement and a little creativity can make saving for that new car, that proverbial rainy day or an active retirement a lot easier … making ‘cake tomorrow’ more of a reality for all of us.

Read more from Crawford in our Clubhouse.

[1] Post Office “UK Households at Risk of Savings Crunch”, June 2014

[2] OECD Economic Outlook 2014; UK Office for National Statistics

[3] IB Times “Millions of UK Households Have Only £250 in Savings” November 2013, http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/hsbc-research-savings-money-emergency-month-salary-521855

[4] Source: www.finra.org

[5] The New Yorker ‘Don’t – The Secret of Self-Control’, May 2009

[6] Beaver et al, 2008; Beaver et al 2009

[7] Shefrin, H. “Born to spend: How nature and nurture impact spending and borrowing habits.” April 2013, Chase Blueprint

[8] http://www.phoenixfocus.com/2014-03/whats-your-money-personality/

[9] Knutson, Rick, Wimmer, Prelec, Loewenstein ‘Neural Predictors of Purchase’, Neuron 53, Jan 2007; Carnegie Mellon press release ‘Spend ‘til it hurts: Researching the pain of paying’ http://www.cmu.edu/homepage/practical/2007/winter/spending-til-it-hurts.shtml

[10] John Tierney ‘The voices in my head say buy it! Why argue?’ January 2007, New York Times

[11] See Vallacher and Wegner’s Behavior Identification Form: http://www.wjh.harvard.edu/~wegner/BIF.htm

[12] Ulkumen, G., Cheema, A. “Framing Goals to Influence Personal Savings: The Role of Specificity and Construal Level” Journal of Marketing Research Vol. XLVIII, December 2011

[13] Cronqvist, H., and Siegel, S. “The Origins of Saving Behavior” 2011, Working Paper Claremont McKenna College

[14] Moffitt et al “A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety” PNAS 2010

[15] Moffitt et al “A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety” PNAS 2010

[16] NS&I March 2013: http://www.nsandi.com/media-centre-savings-levels-britain-highest-amount-recorded-2004

[17] Soman, D. and Cheema, A. “Earmarking and Partitioning: Increasing Saving by Low-income Households” 2011, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol XLVIII, S14-S22

[18] LearnVest “The Winner of the February Call to Action” March 2014 http://www.learnvest.com/2014/03/the-winner-of-the-february-call-to-action/

[19] http://personal.natwest.com/personal/savings/tools-for-savings/savings-goal-demo.html

[20] Leadbeater, C., Elliott, A. “A Better kind of banking”, RSA, Autumn 2013; Fairbanking Foundation “Reaching for the Stars” Autumn 2013

[21] Ipsos MORI survey conducted with 1,188 RBS/Natwest customers who have a Your Savings Goal. Fieldwork was conducted in October 2013.

[22] http://www.saffronbs.co.uk/savings/plan-save-get-your-goal.php; https://www.plansaveget.saffronbs.co.uk/

[23] Fairbanking Foundation “Reaching for the Stars” Autumn 2013

[24] www.mixergy.com, Andrew Warner “Interview: HelloWallet: 0 to 300,000 Paid Subscribers In 5 Months – with Matt Fellowes”, 29th November 2011; http://hrpost.hellowallet.com/engagement/webinar-recording-tips-for-effective-employee-emails/

[25] Fidelity Investments, a global financial services provider partnered with LearnVest, a financial planning company to create ‘MoneyFirsts’ in December 2013.

[26] http://www.learnvest.com/2014/05/money-habits/

Newsletter

Enjoy this? Get more.

Our monthly newsletter, The Edit, curates the very best of our latest content including articles, podcasts, video.

Become a member

Not a member yet?

Now it's time for you and your team to get involved. Get access to world-class events, exclusive publications, professional development, partner discounts and the chance to grow your network.