Unfortunately history does not seem to record whether, one morning in 1771, the one thousand German aristocrats who received an unsolicited sample with a circular letter from British potter Josiah Wedgwood were astonished. It would be fascinating to know whether the language seemed strange to them, how it was packaged and whether Josiah's designs appealed to the Germanic taste of their families. We do know, however, that the huge risk (a princely £20 per package) elicited a fast response, which quickly paid back, and that within two years, all but three of those that had purchased had paid in full.

A factor in this success was Josiah's long-running after-care package. It included a 'satisfaction or money back' guarantee, free shipping and the willingness to replace any broken item without question. Among the first recorded examples of service support to product purchase, it was one of the distinctive components of his approach and contributed to the success of this 300-year-old premium brand. We know a little more about the reaction of rural American housewives, 100 years later, to Henry Heinz's attempts to create tasty processed food. They appreciated the consistent quality that made his products stand out from commodities, and grew to rely on it to save them time in a busy, gruelling lifestyle. Yet his success was also due to the service support that Henry's growing band of sales travellers offered the retailers who sprung up around the fast spreading American train network.

They helped little dusty general stores with managing inventory, choosing advertising and sprucing up merchandising displays. By the late 1880s, they taught point-of-sale marketing, showed how to display and provided free advertising copy. As with any good service package, the detail was impressive. Alongside requirements for each salesperson (of which there were 350 by 1901) to 'wear a Derby, stiff collar and company pin' were instructions to carry a clean white cloth to dust Heinz products, allowing them to 'rearrange displays' and put competitor products behind theirs. So in Hollywood's westerns, at the back of all those shot-up grocer's stores, should perhaps be a neat traveller demonstrating one of the earliest examples of service helping the battle for shelf space.

One hundred years later still, with the service sectors of the developed economies storming ahead, a range of entrepreneurs managed to create entire service businesses that appealed to the growing middle classes and became brands in their own right. They include Richard Branson's heroic achievement of creating a truly different airline experience, and Howard Shultz's obsession with making Starbucks into the 'other place' for busy Americans. For them, distinctive service was not just a component in a product brand, it was the essence of their business.

Yet, if there is such a long, rich history of service being used in different ways to create distinctive, durable brands, why do so many professional marketers find it such hard work to think through the role of service in their value proposition? Why do many groan when there is yet another book on customer service and when they are hit by the latest fad (currently 'customer experience management')?

And why is there such nonsense talked and written about service?

PERHAPS IT'S THAT AFTER-CARE AND MAINTENANCE ARE UNDERVALUED?

To many marketing people, after-care is a humdrum, steady but separate part of their business, run by bears of little brain. It is neither sexy nor strategically challenging and often an afterthought in their plans. As a result, it can be ignored and neglected.

Yet it is an important ingredient in customer satisfaction and has a discernible impact on repurchase intent. As David Edgerton has pointed out, in his remarkable book The Shock of the Old, technology is often presented to modern audiences in a distorted, 'innovation centric' style that undervalues the importance of after-care. Some manufacturers earn valuable extra margin from maintenance and warranty; and in many parts of the world there are large and sophisticated markets in after-care alone. Unipart is just one of many firms to have made its fortune by leading this field. Its outsourcing processes, for instance, are highly sophisticated and very lucrative.

Marketers need to get their minds around the implications of this undervalued capability to their company's products. For instance, there comes a point in many technologies (televisions for instance) when they are stable enough for customers to buy without fear of breakdown. This is an unarticulated, intuitive process that grows through word-of-mouth and product use. It changes the perceived value of after-care and can have a dramatic impact on earnings if not handled properly.

IS IT BECAUSE SERVICE PEOPLE CAN TALK SUCH DRIVEL?

I'm afraid that I still do not know whether my dislike of 'guru' Tom Peters is because of his style or message. Gaining profile in the 1980s with his 'excellence' book, his hectoring speeches seemed, to my English taste, to be too much like those of a religious evangelist than a pragmatic businessman. While I respect the fact that he made himself enormously wealthy, I remain sceptical of the claim by him and his ilk that 'all you need to do is give the customer what they want and exceed their expectations'. (Peters has gone further than most by proclaiming that we should 'wow' customers and reinvent our companies around them.)

I sometimes wonder if such people have ever served a real human being. While people can be delightful, generous, polite and endlessly fascinating, they can also be awful. Consumers can lie, cheat, steal and avoid paying bills. Early in my career, when working in the chairman's office of BT, I was lumbered with a 'high-level complaint'. A woman was making headlines because she was unable to pay her bill and stay in touch with her daughter's medical team. I remember her reverse-charge call from one of the old red telephone boxes, during which she offered to put her 12-year-old daughter on the line to confirm that she had only a short time to live. The local people had done enormous amounts for her over the years and so, it turned out, had all the public bodies. I remember my shock at finding out that the illness was benign and exaggerated. Our service people had to hold the line against a woman prepared to lie in front of her child in such an appalling way.

Business buyers can be just as bad. Although many are a joy to work with, some are pompous, arrogant and overbearing. Others are plain crooked. So businesses need mechanisms, designed by marketers, to engage with and respond to both the best and the worst in our natures, or costs will increase astronomically. Service organisations should not be geared to blindly give them everything they want or to continually exceed expectations.

Surely the essence of marketing is that we interpret insights into needs, using them to craft propositions that excite buyers? It is simply not good enough to say that we will put the customer at the centre of our organisation, meet their hearts' desires and exceed their expectations. It needs the hard-headed insight from clear-eyed marketing people to craft a profitable response to human needs. Even with services, customers' response ought to be: 'I didn't realise I wanted that but, now I see it, I'm delighted to pay for it.'

PERHAPS SOUND CONCEPTUAL TOOLS ARE NEEDED?

In a busy job it is difficult to stay up to date with developing concepts and reliable marketing techniques. This is made harder by the array of proprietary models flogged by different agencies and the 'thought leadership' of endless consultancies. It is no wonder that, marketers find it hard to stay on top of specialist areas like service, as well as their own field.

Amidst the dross though, a number of reasonably reliable techniques have been pioneered by academics. Texas professor Leonard Berry and his colleagues developed, for example, the 'GAP' model. It identifies six fault lines in an organisation's service, and can be used as an effective tracking tool ('servqual'). There is also: 'the industrialisation of services' (Levitt), 'the service profit chain' (Sasser), the 'loyalty effect' (Reichheld). and 'zones of tolerance research' (Ziethaml). A number of these can be used to help develop thinking and to create useable insights if backed by decent analysis.

The Goods/Services Spectrum

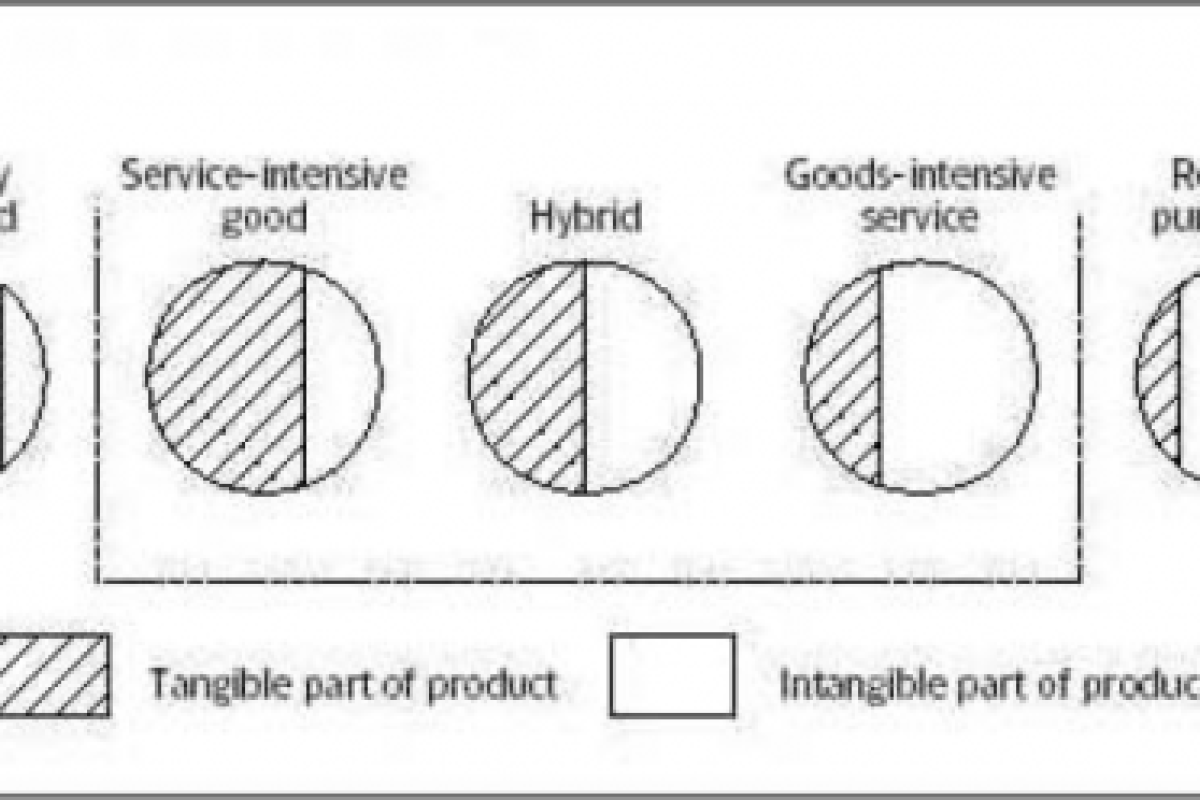

For instance, a really useful way in which the detail of different offers can be designed was suggested by a smart marketer called Lynn Shostack when she was VP of the Banker's Trust of America. Her 'goods/services spectrum' (Figure 1) was published in a 1977 article called 'Beyond product marketing', which should probably be required reading for every marketer in our service-dominated economy.

Using one of the standard methods to plan the 'augmented' features of a product, Figure 2 represents a product with a maintenance, guarantee, warranty or 'service support' package. These act as an emotional reassurance to the purchaser of the enduring provision of product benefits. The promise is: 'Don't worry, if it goes wrong we'll repair it'.

Figure 3, though, represents an evolution where suppliers begin to build service into the product concept (preventative maintenance in computers, for instance). In this model, service has become an augmented component of the product offer. The promise is: 'we have engineered service into our product so that it will almost always be available to use'. Figure 4, by contrast, represents a position at the centre; what Shostack called a 'hybrid'. Here people are buying a mix of the tangible and intangible, commonly found in industries that offer high-volume, low-margin products.

Although this method might seem a little too detailed and pedantic to some, it illustrates the time and attention that many put into thinking through the role of service in their offer.

It would be a mistake, though, to give the impression that the evolution of offers in any market is only from left to right, from products to services, as some service enthusiasts do. There are many examples of the reverse: products or technologies replacing services. These range from very simple propositions (as when the British population replaced laundry services with automatic washing machines 50 years ago) to more complex modern services (like self-service airline check-in and web-based professional services). This substitution effect is dependent on two things: the difference in the perceived cost of changing to new technology and the education of the user to adopt it.

There is now a whole industry investigating the automation of and 'co-production' of services. It would be better led by experienced marketers who know how to create appealing propositions, to help customers over technology fear and to use communications to allay any scepticism that these initiatives are just to save the company costs (even if they are).

IS IT BECAUSE SERVICE DIFFERENTIATION IN MATURE MARKETS REQUIRES RADICAL REALIGNMENT OF THE COMPANY?

When a market matures it can be sudden, traumatic and devastating for the suppliers in it. Several will be damaged by trying to market or sell their way out of slowing demand. Others will try to restructure their business, some reaching for a form of service to alter the fundamental offer. Often, though, it takes completely new entrants to take advantage of new service opportunities (see box on page 32 for examples).

Perhaps it is no coincidence that the people who have used service to create viable businesses and brands have generally been the businesses' leaders. From historical Figures like Wedgwood and Heinz, to entrepreneurs like Branson and Shultz, they direct all the elements of their organisation at creating an enduring, distinctive offer, whether or not they contain physical or intangible components. In more established businesses, it has been two world-class CEOs (Jack Welch when at GE and Lou Gerstner of IBM) who have demonstrated how to shift a massive organisation to exploit service opportunities. In both cases, they appointed a strong general manager to lead all the components of this new profit centre, generally from outside the existing service organisation.

Often this is such a change that marketing people do not have the political clout to see it through, or even influence it. Worse, though, it seems that many do not have the training, tools or experience to design the role of service in their brand, product or businesses. This is tragic in an economy that is now approximately 70% services. Marketers have demonstrated that they can create wealth for shareholders by handling intangible propositions like brand, celebrity endorsement or lifestyle aspiration. It is time they became as competent in services.

SERVICE IN MATURE MARKETS

Royal Shave

In the 'male grooming' market manufacturers have invested in different ways to produce razors that give a closer shave; producing two, three or even four blades. Each creates a new price point for the products but the price per shave remains very low. Yet New York's Malka and Myriam Zaoui have created 'the art of shaving', a premium and expensive service. In addition to a range of innovative products, the company offers a shave with a wet razor in its Manhattan-based 'barber spas'. Its 'Royal shave' combines master barber services with aromatherapy to produce a shave at a cost that is many times the price per shave of a man's own. It is sold as a unique and special service experience, and is quickly being franchised across the US.

System integration services

'System integration' services in the IT industry is an example in business-to-business. During the early decades of the computer industry, the processing power of computers was bought through proprietary mainframe systems; to automate a specific task, like payroll or accounting. However, new industry standards soon enabled these machines to communicate with each other, technology fell in price and, worst of all, customers started to demand that computing related much more to their businesses. So, rather than just supplying updated machines, leading suppliers began to offer an open-minded review of all the customer's existing technology and how it suited developing needs.

In this fast maturing market, service, rather than machinery, was used as a means to provide the processing power that customers had always been after. Several established suppliers were effective at this but new service entrants, like Accenture, cantered through to dominance.

Differentiation in after-care service

Some firms try to use variations in industry standards of after-care in order to differentiate their product in a mature market. A famous example is when, in 1994, the Korean car manufacturer Daewoo entered the maturing British new car market. Daewoo, unknown to this brand-loyal market, intended to gain 1% share through a different approach. Apart from a highly visible brand launch, the company aimed to keep control of customer contact, engineering the purchase experience around its buyers.

For instance, it operated only through owned outlets placed in retail parks, which it stocked with service people trained to give accurate answers to questions and not 'pushy sales people'. These 'service centres' contained a host of innovative packages including, inter alia:

interactive in-store displays, crèches and fixed, no-haggle prices. The entire package was integrated with high-profile marketing and achieved its entry objectives.

Figure 1: The goods/services spectrum (Leonard & Parasuraman, 1991)

Figure 2: Models of service 1: High product content

Figure 3: Models of service 2: Service used to differentiate a product

Figure 4: Models of service 3: Low-margin product sold through a service environment

REFERENCES

Berry, Leonard & Parasuraman, S. (1991) Marketing services: Competing Through Quality, Free Press.

Heskett, James L., Jones, Thomas O., Loveman, Gary W., Sasser Jr, W. Earl, & Schlesinger, Leonard A. (1994) Putting the service value chain to work, Harvard Business Review, Mar–Apr, pp. 164–174.

Levitt, Theodore (1976) The Industrialization of Services, Harvard Business Review, 54 (5), Sep–Oct, pp. 63–74.

Shostack, G. L. (1977) Breaking free from product marketing, Journal of Marketing, 41 (2), pp.73–80.

Reichheld, Frederick F. (1996) The Loyalty Effect: The Hidden Force Behind Growth, Profits, and Lasting Value, Harvard Business School Press.

Ziethaml, Valerie (2000) Services Marketing, McGraw-Hill.