'Habits form the bedrock of everyday life; without habits, people would be doomed to plan, consciously guide, and monitor every action, from making that first cup of coffee in the morning to sequencing the finger movements in a Chopin piano concerto.'[1]

This article is Part One of a three-part series looking at habits in depth. Part One examines the theory behind habit formation and what we can do to put a stop to stickily engrained bad habits. In Part Two (to be published later this year) we go on to explore ways of creating new (better) habits in our lives, like committing to take regular exercise, keeping in better touch with friends and family, eating more healthily, or reading more often. Part Three looks at how we can measure habits and habit strength.

Part One: changing sticky habits and making the subconscious, conscious:

THE POWER OF HABIT

Much of our lives are governed not by our conscious decisions or thoughts, but by our habits, whether they are behavioural, emotional or even linguistic. Once embedded the very stickiness of habits means they're tenacious and hard to dislodge. And even if we are aware that they are bad for us we find it difficult to stop doing them. In 1954, Iain Macleod the UK Health Minister of the time and habitual smoker, famously chain-smoked through a press conference about the dangers of smoking and lung cancer, despite being convinced of the link between the two.

We can also be quite unaware that some of our actions are habitual. For example, we might make a cup of tea and add a couple of biscuits on the side (not realising that we add that couple of biscuits every time we make a cup of tea), or we might unknowingly use particular expressions so often that we drive other people mad (if we were ever to read a transcript of our conversations we'd probably be horrified to hear the number of 'you knows' or 'likes' or ‘super-this’, ‘super-that’ that punctuate our everyday lexicon), or each morning at work we might find ourselves 'unable to function' without a first cup of coffee. These are all habitual behaviours that have become fixed in our neurological patterning. Sometimes our habits are so embedded in our subconscious that they get us running on autopilot. When we're driving a familiar route, for instance, we might have no conscious recollection of any details of the journey, or trolleying our pre-ordained circuit of the supermarket we probably won't notice anything about the other people we pass and we're totally thrown if the layout of the store and product display has been altered.

WHY HABITS FORM

Habits serve a significant purpose – certain behaviours become automatic mostly to make us more efficient. We can all recall being in a totally new environment – perhaps working abroad, or visiting friends with a very different lifestyle. It’s often disorientating and awkward, everything seems to take much longer because every single choice and behaviour requires 100% of our attention. Eventually though, new habits develop which make our lives much smoother and more fluid – and these new habits actually free up our minds so that we can do other things in parallel. As Theodore Roosevelt said 'Habit and routine free the mind for more constructive work.'

HOW HABITS FORM

Our habits are deeply engrained in our brain and muscle memory so much so that they become automatic. We can define this autopilot behaviour by three qualities:

- Minimal awareness – we can carry out the action without needing to pay much attention to what we are doing

- Efficiency – we can carry out a habitual behaviour in parallel with other activities demanding more attention

- Lack of control and conscious intention – we do things without actual conscious intention or desire and it’s actually difficult to stop yourself from doing them or to do them differently[2]

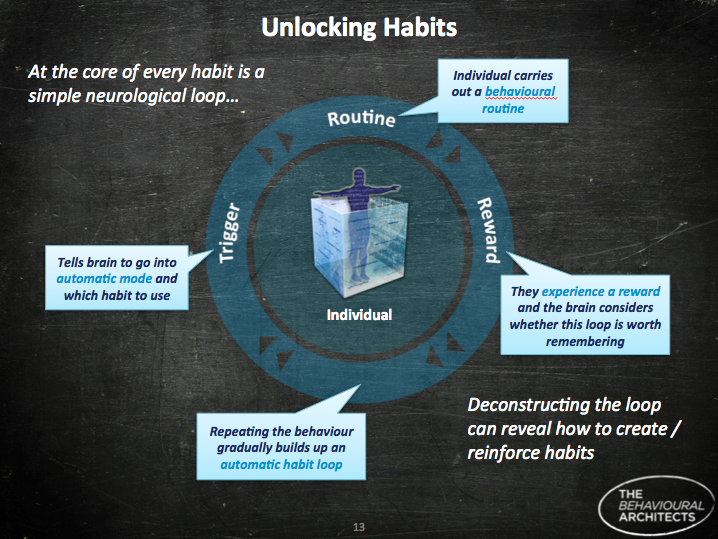

Habits are believed to be formed through the interaction of three elements. Charles Duhigg, author of the book ‘The Power of Habit’[3] defines these three as:

- Trigger or cue

- Routine

- Reward

Each element plays a particular role in embedding the habit (also see diagram below).

-

The trigger or cue is the signal to carry out the habitual routine for example, leaving your trainers by the side of your bed might be the cue you need to get up and go running first thing in the morning, and taking a plastic bag along with you on a dog walk is the cue to pick up after your pet. The trigger can also be a preceding action, perhaps a habit in itself, creating a chained series of actions, or even a ritual, all of which are usually automatic and carried out without thinking.

-

A habit also becomes embedded simply through the act of repetition – doing an action over and over again – often in the same environment, so it becomes routine and engrained in our muscle memory; for example, driving, brushing our teeth or riding a bike all become habitual behaviours. When we first tried them, they were tricky to master (some trickier than others!), but after carrying them out day after day, they became easy and automatic. Scientists say that once we master a new task or skill, our brainwaves slow down – we become more efficient at carrying out the task and therefore have less need to think consciously about it.[4]

- Finally, for some habits, there is also a reward attached, sometimes simultaneously or following the action. The reward can be tangible – tucking into a bacon sandwich after going for a long arduous run – or physiological - the dopamine release which provides the brain with a ‘feel-good’ reward during or after an activity, or even subconscious – a sense of achievement at the end of a routine task.

Each of these elements; the trigger, the routine and the reward, combine to fix the habitual behaviour in place. And once fixed, behaviour is very difficult to change or stop. A diary-based study[5] conducted by researchers at Duke University, North Carolina demonstrated that around 45% of everyday behaviours by students and other members of the community involved in the study were based on habit (routine behaviours – usually performed in the same location) rather than deliberate thoughtful actions. Charles Duhigg usefully deconstructs his own difficult to shift afternoon cookie habit loop in his book and it's the perfect illustration of the trigger, routine, reward structure on which our habits hang. Every afternoon at the office he would go to the cafeteria and eat a chocolate chip cookie which caused him to gain weight. He knew it was a 'bad' habit but it was a habit that he found hard to kick. The only way to do it, he realised, was to identify exactly how the habit worked. He soon discovered that the trigger for his cookie consumption was time: between 3pm and 3.30pm each day he walked to the cafeteria. The routine behaviour was the cookie consumption - and his 'aha' moment here was discovering that the cookie wasn't actually the reward. This made it much easier to kick the habit of course. The actual reward was the chance to socialise with his colleagues. Once he realised this, his new routine behaviour was simply to walk over to his colleagues' desks at the same time in the afternoon and have a cookie-less chat. A new less weight compromising habit had been formed.

Source: Based on Charles Duhigg's 'Habit Loop', ‘The Power of Habit’, Random House, 2012

As Duhigg shows, there are strategies we can apply to help to break habits and change our ways for the better once we understand the trigger, routine and reward looping of our habits. And our awareness of unconscious, habitual behaviour can also be heightened by the use of clever, innovative design which can surface our habits - moving them from our subconscious to our conscious mind. We look at a few innovations in the rest of this article

THE HONKING HABIT

Anyone who has visited India will know that the urban roads are crazy and chaotic. Drivers are in the habit of using car horns frequently (for almost every occasion in fact) often 'honking' to signal driver intention or simply their presence on the road, rather than in anger, and this obviously creates a noisy, frustrating driving experience. Decibel levels are often well past the threshold for human pain. Anti-honking campaigns to raise awareness have failed in the past and Audi responded to the honking problem by making their car horns both louder and more capable of withstanding the driving demands of the Indian consumer. Audi's India head Michael Perschke said 'You take a European horn and it will be gone in a week or two. With the amount of honking in Mumbai, we do on a daily basis what an average German does on an annual basis.'[6]

Whilst drivers may well feel safer on the road if they can honk to announce their presence on it, there is a growing problem of hearing loss in urban centres in India and traffic noise is responsible for much of it. One study into the problem showed that 75% of traffic officers in Southern Indian cities had permanent damage to their hearing caused by their daily exposure to traffic. So no harm then in the work of Indian branding and behavioural design consultancy, Briefcase, who tested a more behaviourally orientated solution to this problem by attempting to reduce honking. Their aim was simply to make drivers more aware when they had honked. They worked with Honda to add a simple red button to the dashboard. When drivers honked their horn, this button bleeped and flashed continuously until they turned it off. They also printed a little frowning face on the button. They added this design to a set of Honda City and Honda Swift cars which they then tested with 30 drivers over 6 months. The Horn Reduction System reduced honking for all drivers by an impressive 61% on average.[7] The designers speculated that this removed much of the indiscriminate, unnecessary honking from the driver. (Watch Briefcase's own animated film below: http://www.behaviouraldesign.com/2013/06/03/bleep-horn-reduction-system-video/)

Their design worked, not because it required drivers consciously to reduce the frequency with which they used their car horns, but because it brought the action of honking to the driver's conscious attention and then disrupted the honking behaviour by making drivers turn off the (annoying) bleeping and flashing button in the car. The presence of the frowning face also made use of injunctive social norms – things we know we shouldn’t do in society – to remind drivers that honking their horn was largely an anti-social action. The device also cleverly tracks how much drivers use the horn – silently observing and tracking behaviour – so usage analysis can rely on actual behaviour rather than subjective self-reports, providing the designers with far more accurate records of behaviour.

Their design worked, not because it required drivers consciously to reduce the frequency with which they used their car horns, but because it brought the action of honking to the driver's conscious attention and then disrupted the honking behaviour by making drivers turn off the (annoying) bleeping and flashing button in the car. The presence of the frowning face also made use of injunctive social norms – things we know we shouldn’t do in society – to remind drivers that honking their horn was largely an anti-social action. The device also cleverly tracks how much drivers use the horn – silently observing and tracking behaviour – so usage analysis can rely on actual behaviour rather than subjective self-reports, providing the designers with far more accurate records of behaviour.

MINDLESS EATING

Another study looked into the absent-minded eating of popcorn at the cinema. We often eat mindlessly, even when we aren’t really hungry. Researchers David Neal and colleagues conducted an experiment to identify the factors that disrupted or maintained the habit of eating popcorn. They took 158 participants into a cinema to watch movie trailers whilst also giving each of them a bucket of stale popcorn to eat. Participants agreed that eating stale popcorn (as opposed to fresh) gave limited satisfaction, but researchers found that how much of the popcorn they ate was dependent on another factor. One group was told to eat the popcorn normally (using their dominant hand) and a second group were asked to eat using their non-dominant hand (so if someone was a right-handed eater, they had to use their left hand to eat the popcorn). They found that those using their non-dominant hand ate significantly less popcorn than those using their dominant hand. It worked because eating with their non-dominant hand was not an automatic, habitual behaviour and so required conscious attention. [8] 'Habit change may require interrupting fluid habit execution, 'the researchers said.[9] (Of course it should be pointed out that regardless of which hand they used, all the participants consumed some of the stale popcorn, because the habit of eating popcorn - any kind - when you're at the movies is so deeply engrained!)

Another study into mindless snacking was conducted by behavioural scientist Brian Wansink who looked at how to make consumers more conscious of the amount they were eating by using colour to alert the brain. He found that inserting edible serving size markers – dyed red – into tubes of crisps helped to curb overeating among 98 college students. In addition, the dividers made students much more accurate in estimating how many crisps they ate. In the first study, the red markers were interspersed at intervals, each designating one suggested serving size (equating to seven crisps) or two serving sizes (14 crisps).  Students who were served tubes of crisps containing the red marker crisps consumed about 50% less than the control group.

Students who were served tubes of crisps containing the red marker crisps consumed about 50% less than the control group.

The red dividers also led to a more accurate estimation of actual consumption. On average, students eating the crisp tubes without dividers underestimated their intake by 12.6 crisps whilst those with red dividers were off by less than one crisp.

Wansink commented 'An increasing amount of research suggests that some people use visual indication - such as a clean plate or bottom of a bowl - to tell them when to stop eating. By inserting visual markers in a snack food package, we may be helping them to monitor how much they are eating and interrupt their semi-automated eating habits.' [10] So giving feedback allows us to consciously measure how much we are eating and make us more aware of the amount we have consumed.

LET THERE BE LIGHT!

Not only do we sometimes mindlessly over eat, but we often needlessly waste energy in the home simply because we are not in the habit of turning off appliances. We habitually leave the TV on standby or forget to turn off a lamp. Design can help by alerting our conscious minds to our neglectful behaviour.

Dr Marc Hassenzahl is Professor for Experience Design at the Folkwang University of Arts in Essen, Germany. He studies non-coercive design and has developed a number of solutions to make us more conscious and aware of our unconscious behaviour.[11]

-

One is the ‘Forget-me-not’ light: a reading lamp that has to be periodically touched to stay on, making users conscious of the fact that the light is providing light for them. After being switched on the lamp gradually closes its petals like a flower (see image), and its light slowly dims. If one of the petals is touched the lamp re-opens and shines brightly again.

One is the ‘Forget-me-not’ light: a reading lamp that has to be periodically touched to stay on, making users conscious of the fact that the light is providing light for them. After being switched on the lamp gradually closes its petals like a flower (see image), and its light slowly dims. If one of the petals is touched the lamp re-opens and shines brightly again.

- Another is the 'Never Hungry Caterpillar' - an extension cable that remains still when a TV or similar device is on, but goes nuts when switched to standby, twisting and turning and appearing to writhe in pain and agony. The movement is intended to catch our attention and bring our neglectful behaviour into our consciousness, and it's a far more effective method than the passive red standby light on the TV. This alternative design creates a visible, movement-based, highly emotional cue to tell us that we are wasting energy. We can almost feel the caterpillar's pain.

Hassenzahl says 'Contemporary design is not used to making things troublesome. We are used to making things convenient. We are used to meeting the needs of our clients whether it is good for them or not. But what we actually need to instil change is ‘friction'.'

Conclusion

Repeat after me: trigger, routine, reward; trigger, routine, reward; trigger, routine, reward = HABIT.

The behavioural sciences have given us a simple model for understanding the architecture of how and why habits are formed. By thinking about or surfacing an existing or desired habit loop and defining the triggers or cues that establish the behavioural routine to the psychological rewards that cement the circuit, we can see how habits can be made or broken by using behavioural design for example, or by changing the environment. And because habits are the backbone of all of our behaviour, this gets everyone excited.

You can read the full three-part report by downloading the pdf below.

Read more from Crawford Hollingworth

[1] Neal, D., Wood, W., Quinn, J. ‘Habits – A repeat performance’ 2006, Current directions in Psychological Science, Vol 15, No. 4, p198

[2] Verplanken, B., Wood, W., ‘Interventions to break and create consumer habits’, 2006, Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, Vol. 25 (1), Spring, 90-103

[3] Charles Duhigg, The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business, Random House 2012

[4] New Scientist, ‘Habits from when brain waves slow down’ 26th September 2011

[5] Quinn, J.M., & Wood, W. “Habits across the lifespan.” Unpublished manuscript, Duke University. See also Wood, W., Quinn, J.M. & Kashy, D.A. “Habits in everyday life: Thought, emotion, and action” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 1281-1297

[6] Globe and Mail ‘Horn OK please? - Extra-loud car horns lead to growing problem of hearing loss in India’ 10th September 2012

[7] http://brief-case.co/bleep.html

[8] Neal, D., Wood, W., Wu, M., and Kurlander, D., ‘The Pull of the Past: When Do Habits Persist Despite Conflict With Motives? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 2011, DOI:10.1177/0146167211419863

[9] http://bps-research-digest.blogspot.co.uk/2011/09/want-to-eat-less-try-using-your-non.html

[10] Geier, A., Wansink, B., & Rozin, P., ‘Red potato chips: Segmentation cues can substantially decrease food intake.’ Health Psychol. 2012 May; 31(3):398-401. doi: 10.1037/a0027221.

[11] http://issuu.com/hassenzahl/docs/create_transformational_products_cr