The weather in the UK this winter has been the wettest since records began and it has attracted a great deal of media and government attention. BBC weather forecaster John Hammond said: 'It is stating the obvious but it is remarkable nonetheless. Our data goes back to 1910 - over a hundred years' worth of data and it's smashed it.'[1] Provisional Met Office figures show that more rain has fallen so far this winter than in 1995, the previous wettest winter on record; thousands of homes have been flooded and many people evacuated. The Met Office also say December 2013 was also the stormiest for 20 years; high winds (up to 140mph at times) and even a few tornadoes tore down power lines, flights and trains were cancelled and infrastructure was damaged.

While there have been some policy errors in managing the problems, the situation has also served to illustrate just how irrational and complex our behaviour and beliefs can be. Our responses to extreme weather and natural disasters are subject to a whole host of different cognitive biases and heuristics which play on our minds, often causing more trouble than they solve.

So what are some of the cognitive biases and heuristics which impact upon our reactions to meteorological drama of this kind? In the first part of this article we look at three – availability bias, optimism bias and gambler’s fallacy and examine how they drive our thinking. In the second part, we go on to analyse some initiatives which harness insights from the behavioural sciences to improve our response to what the weather throws at us.

Availability bias: I can imagine this happening so it must be likely

Availability bias is a mental shortcut we use to assess the likelihood of something happening. When we don’t know the exact probability of an event we try to estimate it by drawing on other similar examples or experiences which come to mind quickly. Most people’s memories are far from perfect and the examples that we draw on are often those which surface easily and these are usually the most vivid, recently seen or experienced events.

Bringing to mind examples of extreme weather events and natural disasters or imagining them happening is a perfect example of the way in which availability bias affects us. In periods of calm, sunny or predictable weather, we sometimes struggle to think of instances of extreme floods, storms, high winds, blizzards etc – and consequently think they are less likely than they really are. Such underestimation can land us in deep water, literally. When the weather's good and we have no recent memory of things being any different, we might buy homes built on flood plains or on the seafront, believing our chances of being flooded to be slim to none.

The reverse is also true. Now, in the midst of one of the wettest and stormiest winters on record, we have no problem imagining how bad the weather can get and probably overestimate the likelihood of apocalyptic events. The media help contribute to our awareness; dramatising the events, using live broadcasts of spectacular weather moments - emphasising huge waves crashing onto seafronts, cars being swept away, deluged houses pitifully sandbagged etc. This kind of coverage encourages us to accentuate the intensity and the ubiquity of it all. The media has also created a whole new lexicon of X-rated weather too: Snowmaggedon, Stormageddon, Snowpocalypse, Polar Vortex, Superstorm, Weather Bomb etc, which helps to cement our acceptance of the likelihood of these things happening. The first question anyone looking to buy a house right now will be asking is 'Does it ever flood around here?' And houses on hilltops will be in high demand (excuse the pun).

Availability bias can lead us to behave very erratically when taking out insurance policies. People often arrange insurance to protect against an event which has just happened because they now have a vivid and recent memory of it occurring. Yet as time passes and the memory fades, people often let their policy lapse, sometimes even believing that it's less likely that such an event will happen again, simply because it has not happened for a while.[2]

A US study to track the proportion of flood insurance renewals found that only 74% of policies were still active after one year, and just 36% still in place after five.[3]

Availability bias also explains why we are more likely to believe in climate change during extreme bouts of weather. A study conducted by Eric Johnson and Ye Li at Columbia Business School surveyed around 1,200 people in the US and Australia in three different studies in order to determine their opinions about global warming. All respondents were asked whether the temperature on the day of the study was warmer or cooler than usual. Respondents who thought the day was warmer than usual were more concerned about global warming than respondents who thought the day was colder than usual.[4] Lead author of the study, Ye Li says 'Global warming is so complex, it appears some people are ready to be persuaded by whether their own day is warmer or cooler than usual, rather than think about whether the entire world is becoming warmer or cooler.'

This idea that people base their attitude to global warming on what's happening with their own local weather system helps to explain why public belief in global warming can fluctuate. And it is a perfect example of availability bias – global warming seems more salient when temperatures or typical weather for that season and in that place are not the norm.

We might also suffer from what is known as confirmation bias when assessing our beliefs about climate change too – when we look for evidence that supports or rejects climate change depending on our own views. Right now, in the midst of all these storms and never ending rain, it is very easy to bring to mind the examples of extreme weather events which meteorologists believe are linked to climate change.

The study also highlighted a particularly interesting political dimension to the subject of perceptions of global warming as it identified democrat supporters in the US as being more likely to 'believe in' global warming than republican supporters. In the US, pre-election public opinion polls usually take place in November when the weather (certainly on the East coast) tends to be colder and when snow and ice seem to contradict the concept of any kind of warming at all. This kind of polling, it is suggested, could be manipulated by those with an interest in rejecting the concept of climate change.

Optimism bias: Always look on the bright side of life

Many of us are often overly hopeful and optimistic, believing bad things will never happen to us despite what the statistics say. Tali Sharot and her colleagues at UCL have conducted many research studies into optimism bias and estimate that around 80% of us are affected by optimism bias, even if we don’t realise it. Moreover, even when we are informed of the true likelihood of an event happening to us, we still only marginally adjust our expectations. For example, participants in one of their studies were asked to estimate the likelihood of 80 negative life events occurring, such as having their car stolen or an accident in the home. When told of the actual likelihood of that event occurring, optimistic participants only marginally adjusted their expectations to the true statistic, still believing that the chances of that event happening to them were lower than for the rest of the population. As Sharot says, people 'leaned a little bit, but not a lot'.[5]

Similarly, we tend to believe that the chances of being affected by a flood or a storm are less than they really are. Qualitative research in the aftermath of a tornado outbreak in the US in 2008 showed that one of the main causes of fatalities was due to optimism bias. 57 people died and 350 were injured when tornado after tornado swept across nine Southern US states. When the National Weather Service reviewed why people had not responded to the tornado warnings they found that a major cause was people’s irrational optimism and their belief that bad things only happen to other people.[6] For example, one Kentucky resident said, 'They [tornadoes] always seem to hit down the road.' And a Tennessee family said they heard on the radio that the tornado was in a town just upstream of where they lived '…but we didn’t think it was going to be here.'[7]

In the same way, we like to believe that floods will never be any worse than they already have been. This, we think, is as bad as it can be. We track the high water marks of every river, lake and sea, basing our beliefs on historical data, optimistically believing that floods are highly unlikely to be any worse than they have been in the past.

We might also overestimate the potential of the development of new technologies to help us guard against the weather, either in prediction power or in technology and infrastructure to protect our houses and land from natural disasters. Yet, while weather forecasting and environmental technology has improved substantially in the last 100 years, it is unlikely to ever be foolproof.

Gambler’s fallacy: We must be due some good weather now?

With week after week of rain and wind, you might be thinking the bad weather can’t possibly last for much longer and that we must be ‘due’ some nice, dry, sunny weather soon. Yet this is an example of another cognitive bias – gambler’s fallacy.

Gambler's fallacy is the misconception that if something has already occurred once or more frequently than normal, then it is less likely to occur again in the future. A typical example is getting a streak of heads when flipping a coin. People misunderstand randomness and think that it should be the turn of tails to 'even it out'. The bias is also called the Monte Carlo fallacy after a 1913 feat in a casino when a roulette wheel landed on black 26 times in a row. Thinking that 'red must be due' most gamblers bet against black...

We think the same about the weather – if we have a week of wet days in the spring or summer we'll most likely consider that we should be in for some sunshine soon. In January if we haven't seen any snow at all we feel a little as if some should be coming - it's winter after all. Whilst when it has already been snowing for a week, we don’t expect it to last.

Howard Kunreuther, Professor of Psychology at the University of Pennsylvania who's an expert on insurance and behavioural economics, has studied our poor attempts at estimating the probability of natural disasters. He says that the language used to communicate risks and the likelihood of a flood or disaster can often be misleading to the average person. 'Scientists often talk about a ‘100-year return flood[8]’, but many individuals do not understand what that means. Some who have suffered a flood believe they will not have another flood for 100 years.'[9]

Making bad weather more salient

Leveraging our cognitive biases to spur us into action

Although the cognitive biases we have outlined above can lead to irrational behaviour, we can also draw on our susceptibility to the same biases to spur us into action. Below we describe three examples of organisations using behavioural science and a better understanding of behaviour to prompt and steer action effectively.

1. Vivid tornado warnings: In the United States 163 people were killed in the 2011 tornado which hit Joplin, Missouri. It was a death toll that could have been avoided. Many of the dead could have been saved had they heeded the tornado warnings and taken adequate shelter and protection. But people didn’t respond to the tornado warnings and take the appropriate action. According to behavioural scientists part of the problem were the dry, dull warnings such as 'You should activate your tornado action plan and take protective action now' which failed to conjure up an image of the dire consequences of a full-blown tornado. Availability bias encouraged people to think a real threat to life was unlikely because they could not imagine it happening. People also tended to seek confirmation from other sources before seeking shelter, such as hearing sirens or even needing to see the tornado approaching with their own eyes before taking action. Ken Harding, a weather service official in Kansas City said, 'We'd like to think that as soon as we say there is a tornado warning, everyone would run to the basement. That's not how it is. They will channel flip, look out the window or call neighbours. A lot of times people don't react until they see it.'[10]

To combat this, the US National Weather Service (NWS) trialled a new style of tornado warning in 2012 in the states of Kansas and Missouri. Their ‘Impact Based Warnings‘ make the warning more emotive and salient, conjuring up images of destruction, reminding people of the real danger to life, and so making the likelihood of a tornado seem higher. They are now using compelling descriptive messages like:

'You could be killed if not underground or in a tornado shelter. Many well-built homes and businesses will be completely swept from their foundations.'

Mike Hudson, the chief operating officer at the NWS Central Region, says 'It paints a mental picture for people in the path of the storm.'[11] Such was the initial success of the two-state pilot, it was expanded to 14 states across Central US in 2013.[12] Of course, there may be a longer term danger that the new style warnings could create a ‘cry wolf’ effect if the threatened tornadoes turn out to be less destructive than anticipated. People may stop taking the warnings seriously and revert to their old ways. We shall see…

2. We’ve noticed that the UK Environment Agency and Met Office have been trying to make flood warnings more salient in order to get people to take action to protect themselves from flooding. After much research and public consultation, the Environment Agency changed the flood warning codes in 2010 to make them simpler and easier to understand. They focused on improving the icons and the language used. The highest alert, 'Severe Flood Warning' comes with an accompanying warning of 'Danger to Life’. This draws on availability bias by making the risk more real and frightening with the intention of prompting people to take action.[13] The media have also been taking a role, making sure to state the ‘Danger to Life’ in any flood news. However, some of the media appear to send conflicting authority messages to these warnings - for instance when we see news reporters reporting from flood scenes standing in – or falling into - the waves!

At times like these a little reframing which puts the UK floods in the context of more extreme human suffering doesn't go amiss. The Daily Hawk pours scalding hot irony all over our watery misery[14]:

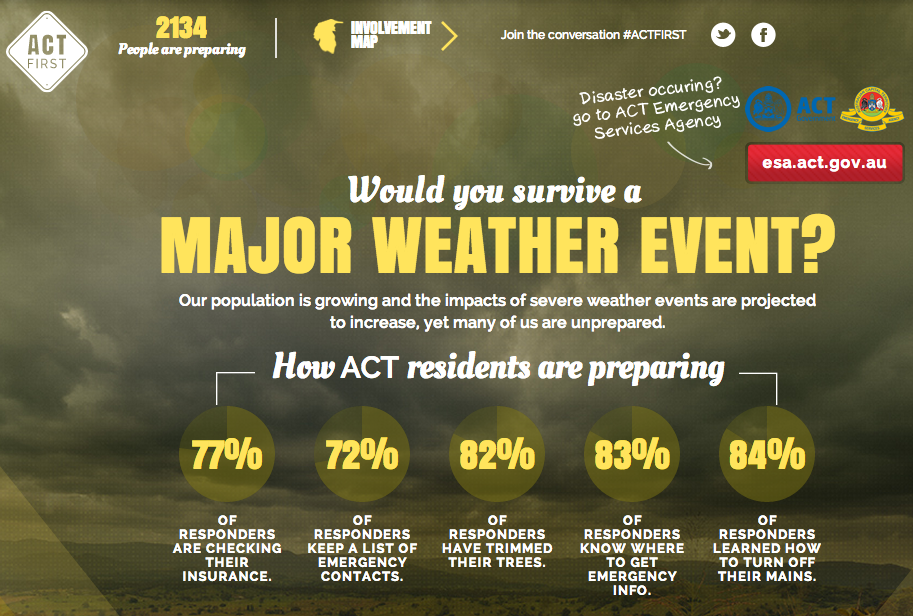

3. Be prepared: On the other side of the world, there has been a clever initiative to get residents of the Australian Capital Territory – the region around Canberra – to take action to make sure they are prepared for extreme weather events such as fires, storms, earthquakes and floods. Called ACT First, it has been developed by Green Cross Australia in a partnership with the ACT Government and support from the Australia National University.[15] The ACT First website (see image below) harnesses a number of behavioural science concepts, including:

- Social norms: the website states what proportion of residents have taken certain steps to be ready for a natural disaster. For example, ‘84% of responders have learned how to turn off their mains’ or ‘73% of responders keep a list of emergency contacts’. We have a natural impulse to do what others do and so tend to follow the majority’s behaviour so these messages are likely to make an impact. They also showcase a range of real case studies, including video interviews and stories of how residents of ACT are getting prepared, with the aim of making other residents feel they should also take some action. We tend to relate well to personal stories.

- Emotive response to imagery: Embedded in the social norms statements are photos sent in by responders, showing that they are ready for anything. For example there is a photograph of some young children proudly holding up their family’s list of emergency contacts and a photo from another responder showing her turning off her mains supply. These images help to get our attention and generate an emotive response which can motivate us to take action. Perhaps seeing a photograph of the children makes us think of our own children and whether we would be ready to protect them in an emergency.

- Tracking residents' actual rather than intended behaviour: The ACT First initiative tracks real actions that residents have taken. It does not poll people, or ask their opinion regarding intended behaviour. This helps to convert attitudes and intentions into real behaviour change, as well as preparing people or extreme weather events.

- Commitment bias: The website prompts residents to make their own emergency plans, chunking down the steps to make it simple to do and helping them to think through each of the components. By thinking through the detail and recording their plans, residents are likely to feel more committed to them. When we have made plans, particularly when we have announced them publicly, we are more likely to see them through.

Conclusion

It's encouraging to see how insights from the behavioural sciences are increasingly informing the design of policy and communications. Although cognitive biases and heuristics like the availability bias and gambler’s fallacy can lead us to behave in erratic, irrational ways, once we understand how they work, we can apply the same understanding to help to correct behaviour, or to purchase adequate insurance cover to protect us or encourage us to respond more quickly to flood or disaster warnings.

After the floods, get ready for the hottest summer on record.....

Read more from Crawford.

[1] BBC News Science and Environment 20 Feb 2014

[2] Kunreuther, H., Sanderson, W., and Vetschera, R., ‘A behavioral model of the adoption of protective activities’ Journal of Economic Behavior and Organisation, 6, 1-16, 1985

[3] Michel-Kerjan, E., Lemonye de Forges, S., Kunreuther, H. “Policy Tenure Under the U.S. National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP)” Risk Analysis, Volume 32, Issue 4, pages 644–658, April 2012

[4] Li, Y., Johnson, E., Zaval, L., “Local Warming: Daily temperature changes influences belief in global warming In Psychological Science (2011)

[5] Sharot, T., Korn, C.W., Dolan, R.J., “How unrealistic optimism is maintained in the face of reality” Nature Neuroscience, October 2011; BBC News “Brain rejects negative thoughts” 9th October 2011

[6] Maryland Weather “Optimism bias could kill you” 17th March 2009 http://weblogs.marylandweather.com/2009/03/optimism_bias_could_kill_you_i.html

[7] US National Weather Service “Super Tuesday Tornado Outbreak Feb 5-6, 2008 Service Assessment” May 2009, p25 http://www.nws.noaa.gov/om/assessments/pdfs/super_tuesday.pdf

[8] The 100 year return flood is a flood that has a 1% chance of occurring in any given year. It does not mean that a flood will only happen once every 100 years. In fact, there could be two 100-year return floods in the course of 2 years for example.

[9] Erwann Michel-Kerjan, Howard Kunreuther (2011), Redesigning Flood Insurance, Science Magazine, 333 (6041), 408 - 409.

[10] Huffington Post, “New Tornado Warnings Based On Storm's Severity Aim To Scare”

31st March 2012: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/03/31/new-tornado-warnings_n_1393994.html

[11] The Daily Beast, “Be Afraid: The Future of Tornado Warnings, 22nd May 2013

[12] http://www.crh.noaa.gov/crh/?n=2013_ibw_info

[13] Environment Agency Briefing Note “Flood Warning Service Improvements Project Introducing our new public flood warning codes”

[14] The Daily Hawk “African Union: We cannot ignore the plight of Berkshire any longer” 14th February 2014 http://dailyhawk.co.uk/2014/02/14/african-union-we-cannot-ignore-the-plight-of-berkshire-any-longer/

[15] http://actfirst.org.au/