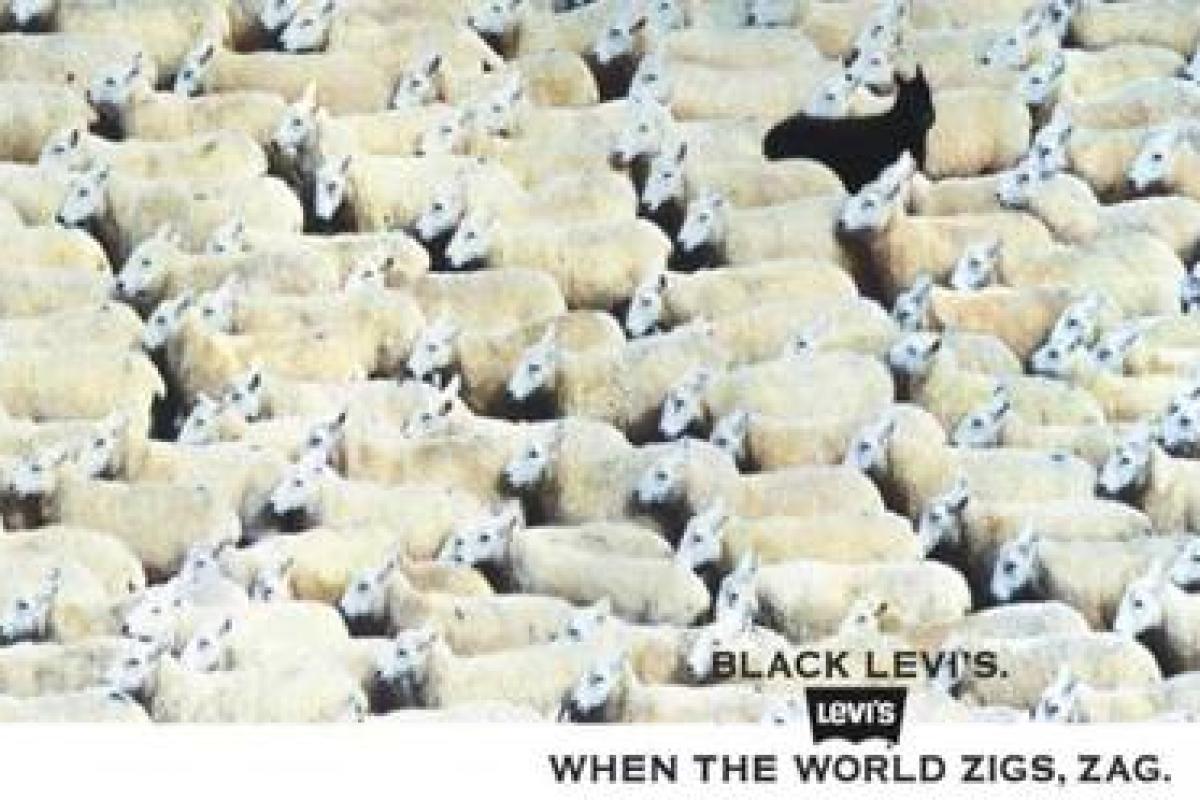

In 1982, Levi’s launched black jeans in the UK. At the time denim was invariably blue so Levi’s wanted to capture the rebellious spirit of those opting for black.

The ad by BBH became a classic.

But the strapline, written by Barbara Noakes, “When the world zigs, zag”, has relevance beyond fashion. Advertisers should heed the brand’s message: distinctiveness is a route to memorability.

And that’s not just hearsay. After all academic evidence shows that brands benefit from subverting expectations.

The original evidence comes from the work of Hedwig von Restorff in 1933. The paediatrician gave participants a list of text: it consisted of random strings of three letters interrupted by one set of three digits. So, for example: jrm, tws, als, huk, bnm, 153, fdy.

After a short pause the participants were asked to recall the items. The results showed that items that stood out, in this case, the three digits were most recalled.

This is known as The Von Restorff effect.

Delivering distinctiveness

Knowing that your ads need to distinctive is helpful, but how do you stand out?

Luckily for you, most brands abide by category conventions. Break those conventions and you become distinctive.

You can see this herd mentality in lager advertising with leading brands invariably associating themselves with football. Such is the clutter that Campaign magazine said they’re “playing 11-a-side on a 5-a-side pitch”.

Lager isn’t the only guilty category. Most brands brag about their success creating a simple way to stand-out: admit your flaws.

But isn’t this risky?

You’re not alone in worrying about admitting weakness.

However, there’s plenty of evidence that this tactic improves your odds of being effective. The original evidence comes from Harvard psychologist, Elliot Aronson.

In his experiment, Aronson recorded an actor answering a series of quiz questions. In one strand of the experiment, the actor – armed with the right responses – answers 92% of the questions correctly. After the quiz, the actor then pretends to spill a cup of coffee over himself (a small blunder, or pratfall).

The recording was played to students, who were then asked how likeable the contestant was. However, Aronson split the students into cells and played them different versions: one with the spillage included and one without. The students found the clumsy contestant more likeable.

Aronson called the preference for those who exhibit a flaw the ‘pratfall effect’. It’s an insight that has occasionally been harnessed to great effect by brands. Think of VW Beetle (Ugly is only skin deep), Stella (Reassuringly expensive) and Avis (We’re only No. 2 so we try harder).

It works because admitting weakness is a tangible demonstration of honesty and, therefore, makes other claims more believable.

Risk-free for who?

I’ve listed a few examples of brands harnessing the Pratfall effect, stretching back to VW in 1959. But there have been tens of thousands of ads since then. Why have only a couple of dozen revelled in their failings?

The rarity is explained by the principal-agent problem, a theory first suggested by Stephen Ross, a professor at MIT. He suggested that there is a divergence of interest between the principal, the brand, and the agent, the marketer. The brand is interested in long-term profitable growth, but the marketer is also interested in safe career progression.

If a campaign flops having used the Pratfall effect it might end a marketer’s career. Imagine you were the marketing director responsible for Reassuringly Expensive and the campaign flopped. You’d be lucky to escape with your job.

Resolving the principal-agent problem

The best way to ensure brands strive for distinctiveness is to popularise the principal-agent problem. If following the herd becomes equated with putting one’s career ahead of the brand’s needs, then it will become a disreputable tactic.

Perhaps then we’ll see more brands admitting fallibilities.

By Richard Shotton, deputy head of evidence, Manning Gottlieb and author of The Choice Factory, a new book on how to apply findings from behavioural science to advertising.