习惯成自然 - When a habit becomes embedded, it becomes your second nature – Confucius

Over the last decade or so there have been breakthroughs in our understanding of habits; insights from the behavioural sciences have been shining an illuminating light on how to explain habits – their causes and how to build or break. Habits form the backbone of consumer behaviour and in many developed markets we struggle as marketers and researchers to both understand them and to break or replace them.

What do we now know about habits?

Much of our lives are governed not by our conscious decisions or thoughts, but by our habits, whether they are behavioural, emotional, linguistic or even our thought processes. Social psychologists estimate that 45% of our daily behaviour is habitual.

A diary-based study[1] conducted by researchers at Duke University, North Carolina demonstrated that around 45% of everyday behaviours by students and other members of the community involved in the study were based on habit (routine behaviours – usually performed in the same location) rather than deliberate thoughtful actions.

What we also know is that major life changes provide amazing opportunities’ to change people habits from leaving home, getting a job, to getting married etc. This brings us to China which, along with other developing markets, is seeing massive changes in how people behave, how they live, work and play – they are hungry for new behaviours, for new habits to help better their lives, to keep up-to-date with peers or to just showcase social standing and individuality. China represents for major brands around the world a rare opportunity to build and nurture new behaviours, new habits.

Putting some context on this change let’s consider just one major social factor that of internal migration from rural to urban to help us grasp the size of this opportunity. With an estimated 340 million citizens reclassified as urban dwellers since 1979, China has seen a wave of migration on an epic scale throughout the last three decades. Combined with strong economic growth and rapid rise of digital, lifestyles have been rapidly developing and changing, particularly for those people moving from rural to urban working environments. And the trend is likely to continue. 90 million more rural residents are being encouraged to move to cities before the end of the decade – a move which translates to more than 43,000 people moving a day - in an attempt to boost domestic consumption growth. This would increase urbanisation of its 1.4 billion population, from the current 53.7% to 60%, by 2020. By 2030, an expected 300 million rural residents will become city dwellers - the equivalent of almost the entire US population moving. [2] Working lives and career patterns are changing too. On average, younger generation Chinese change jobs every six months.[3]

Within this climate of change and progress, Chinese represents a fertile market for creating new habits with the rapidly growing urban middle-class and their insatiable appetite to learn and adopt best practice and behaviours from the world around them. They look both west and east (Japan/Korea) for inspiration and other alternatives in how to improve quality of life and keep up with the times, facilitated by greater disposable income and the need to be more discerning in what they consume with the background of food scandals, environmental pollution and safety issues. They readily embrace change where it adds value to their lifestyle or even a new experience to help make them feel more empowered as individuals or a stronger sense of affinity with the world as a global citizen as China takes centre stage.

So this is a prime opportunity for creating new habits / forming new habits. For example, recent research at The Behavioural Architects Shanghai found that university is a critical period for students to create new eating habits, particularly snacks. Habits established here often have a longer term impacts on behaviour in the future. One student commented:

“What is sold in the campus supermarket is different from what was available in high school…Rather than having those local brand chips or even non-branded ones, I started eating Lay’s chips and have been ever since…”

New habits that have gone mainstream in urban China, and across Tier 1 to Tier 3 cities, include transforming a nation of traditional tea-drinkers to coffee drinkers as coffee and Starbucks café culture became synonymous with a modern identity and aspirational lifestyle.

Another contextual layer that is particularly relevant to China is the extent to which high digital/mobile penetration has transformed the consumer landscape by making it easier to access, purchase and share new products and brands. Mobile convergence is blurring the boundaries between online and offline in consumption behaviour and creation of new habits, where traditional retail and purchase journeys are replaced by the virtual shopper, where watching national TV channels is increasingly the domain of the older generation as younger consumers switch to more engaging (and censor-free) foreign content located exclusively on digital media.

Younger consumers represent the first real generation accustomed to choice and diversification by growing up with technology not as a peripheral component but embedded in the way they manage their lives. This generation is the most globally-minded generation to emerge from China and are very curious and open to trying new things and early adopters of new products, services and new brands – which means being very open to picking up on new behaviours, and new habits.

And the great thing about habits is that once embedded habits by definition become routines, which lack much if any conscious thought – and why they are a marketers dream. So think of habits as sticky: this stickiness of habits means they're tenacious and hard to dislodge. As companies target the (emerging) middle class with new brands and products designed to improve quality of life by changing behaviour they can get unstuck by the stickiness of habits. MNCs promoting modern ways of living may have to revisit global marketing strategy to dislodge culturally-embedded habits. A kitchen-surface cleaning campaign designed to win over young Chinese Mum hand-dish wash users to upgrade to a more modern and effective way of degreasing kitchen surfaces only succeeding in attracting cross-category switchers, rather than the volume opportunity of hand-dish wash upgraders. Despite Mums acknowledging the tensions with everyday cleaning of kitchen surfaces with Hand-Dish Wash liquid (high effort, low efficacy), the versatility and more natural product values of hand-dish wash cleaning was too engrained amongst Chinese Mums culturally and habitually to persuade them to change. This example shows us how hard it is to break existing habits and why we all find behavioural change hard.

A model for thinking about habits and habit formation

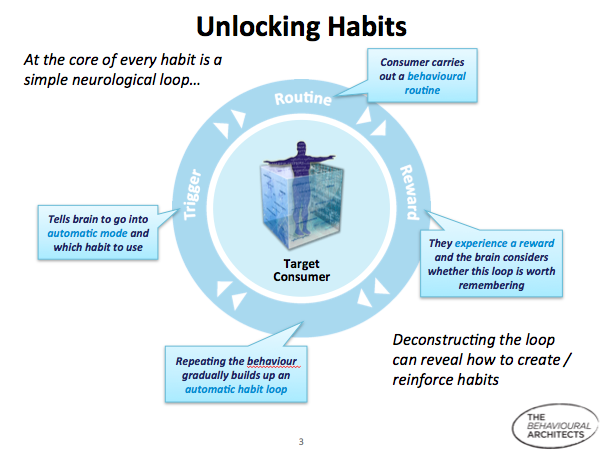

We want to provide you with a powerful model to conceptualise habits, whether you are trying to make, break or measure and that is that habits run in a loop: Habits are believed to be formed through the interaction of three elements. Charles Duhigg, author of the book ‘The Power of Habit’[4] defines these three as:

- Trigger or cue

- Routine

- Reward

Each element plays a particular role in embedding the habit (also see diagram below).

- The trigger or cue is the signal to carry out the habitual routine for example, leaving your trainers by the side of your bed might be the cue you need to get up and go to the gym first thing in the morning. The trigger can also be a preceding action, perhaps a habit in itself, creating a chained series of actions, or even a ritual, all of which are usually automatic and carried out without thinking.

- A habit also becomes embedded simply through the act of repetition – doing an action over and over again – often in the same environment, so it becomes routine and engrained in our muscle memory; for example, brushing our teeth, wrapping dumplings or using our ipad all become habitual behaviours. When we first tried them, they were tricky to master (some trickier than others), but after carrying them out day after day, they became easy and automatic. Scientists say that once we master a new task or skill, our brainwaves slow down – we become more efficient at carrying out the task and therefore have less need to think consciously about it.[5]

- Finally, for some habits, there is also a reward attached, sometimes simultaneously or following the action. The reward can be tangible – tucking into some noodles after a long day at work – or physiological - the dopamine release which provides the brain with a ‘feel-good’ reward during or after an activity, or even subconscious – a sense of achievement at the end of a routine task.

Source: Based on Charles Duhigg's 'Habit Loop', ‘The Power of Habit’, Random House, 2012

Each of these elements; the trigger, the routine and the reward, combine to fix the habitual behaviour in place. And once fixed, behaviour is very difficult to change or stop.

Evidence suggests this type of context change breaks habits because it shakes up the status quo before allowing it to settle, and in the settling process new patterns are shaped. One study asked participants to write an account of a successful or failed life change experience. In analysing each of these stories, researchers found that 36% of accounts of successful behaviour change involved moving to a new location, whereas only 13% of accounts of unsuccessful attempts involved moving. 13% of successful behaviour change also involved altering the immediate environment, whereas unsuccessful behaviour change was always characterised by no changes in environmental cues.[6]

In conclusion – China new urban is wide open to new behaviours, new habits

The behavioural sciences have given us a simple model for understanding the architecture of how and why habits are formed. By thinking about how a habit is created and defining the triggers or cues that establish the behavioural routine to the psychological rewards that cement the circuit, we can see how habits can be made or broken, particularly when the environment and context changes. The huge lifestyle changes occurring every day in China’s growing cities are a huge open door to building new habits for millions. This model of thinking about habits [making, breaking and measuring] is at the core of how the Behavioural Architects approach behavioural change and inspires our unlocking behavioural research methodologies.

By The Behavioural Architects - Shanghai, London, Sydney and Oxford.

[1] Quinn, J.M., & Wood, W. “Habits across the lifespan.” Unpublished manuscript, Duke University. See also Wood, W., Quinn, J.M. & Kashy, D.A. “Habits in everyday life: Thought, emotion, and action” 2002, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 1281-1297

[2] http://news.sky.com/story/1227210/china-growth-plan-to-target-internal-migrants

[4] Charles Duhigg, The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business, Random House 2012

[5] New Scientist, ‘Habits from when brain waves slow down’ 26th September 2011

[6] Heatherton, T.F., and Nichols, P.A., “Personal accounts of successful versus failed attempts at life change” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 1994, 20, 664-675

Newsletter

Enjoy this? Get more.

Our monthly newsletter, The Edit, curates the very best of our latest content including articles, podcasts, video.

Become a member

Not a member yet?

Now it's time for you and your team to get involved. Get access to world-class events, exclusive publications, professional development, partner discounts and the chance to grow your network.