In the last decade we have learnt more about our behaviour than in the last 100 years. We have begun to map the human behavioural blueprint! Whilst much of this learning has been in the offline, ‘real’ world, there is now an emerging focus on how these insights can also be applied to understanding our ever-expanding digital world. This is important because the online environment affects our behaviour in very different ways.

This article is the third of a three part series which overall looks at:

- How and why the online world affects our behaviour in interesting and often surprising ways;

- The general patterns of our behaviour and decision-making online; and that

- How we think and choose online may fundamentally differ from our behaviour and choices offline.

Part 1 and 2 looked at how our interaction in the digital world can lead us to behave in different ways than when we are in the offline world. Part 3 now goes on to analyse two potential impacts of the physical devices we use to access the digital world on our behaviour and consequent decision-making.

1. Touchscreens can trigger psychological ownership

One big difference between online and offline activity is the reduced sensory experience online. Sensory experience is known to be influential in our decision-making. For example, research has illustrated how we can often become more well disposed to a product simply because we have touched it or held it in our hands because that helps to build a sense of endowment and ownership. The endowment effect is well known in behavioural science and shows that we are more likely to overvalue items we own or even perceive as our own.

Although it’s not yet possible to virtually touch something online (there is considerable innovation here) there is new research which suggests that the type of screen we are using can affect our likelihood and willingness to purchase.

Touchscreens – on tablets and smartphones – appear to increase our sense of endowment and ownership. In research recently conducted by Adam Brasel and James Gips, students were asked to choose from a selection of sweatshirts, tents and city tours using different kinds of devices and then rate each product.

They found that using a touchscreen increased both their sense of psychological ownership and willingness to pay. This effect was stronger for more haptic products such as the sweatshirt (see below), compared to the city tour. It also strengthened when the touchscreen device – an iPad – was owned by the participant as opposed to the university laboratory. Ownership of the device was thought to contribute to the feelings of endowment of the product being explored. Adam Brasel highlights the relevance of their findings for online retailers:

“It suggests [companies] should be putting a lot of effort into optimizing their touchscreen versions of their websites, the ones designed for phones and tablets. And that you want as much direct touch as possible, and the pictures of your products to be as vivid and as real as possible because that will generate these ownership perceptions. Retailers should work with that and not necessarily against it. It does seem like e-commerce is moving toward tablets and other touch-based devices, so this effect is only going to get more important in time, rather than less.”

“Sense of ownership” effects will be an important design consideration for e-commerce platforms as tablet penetration increases , particularly in the context of the growing ability for individual consumers to design and customise products online.

2. Your iPhone may be turning you into a wimp

The trend towards smaller devices such as smartphones and tablets may have other implications for our behaviour. Psychologists Maarten Bos and Amy Cuddy at Harvard University have been studying the effects on our behaviour from using different size screens. Prior research by Cuddy and others has suggested that our body position and stance can affect our feelings of confidence:

- A stance or pose which takes up physical space – leaning back or holding our arms out wide or high – has been shown to prime people to be more confident or assertive.

- Conversely, hunching over and taking up a small amount of space has been shown to make people less assertive.

They applied this general finding to study the impact of different body postures in operating everyday technology - from smartphones and tablets, through to laptops and desktops. Using a desktop means we tend to adopt a more expansive body posture, something along the lines of a victory pose or putting your feet up on the table, in contrast, using a smartphone constricts our body posture, causing us to hunch our shoulders, look down and tense our neck.

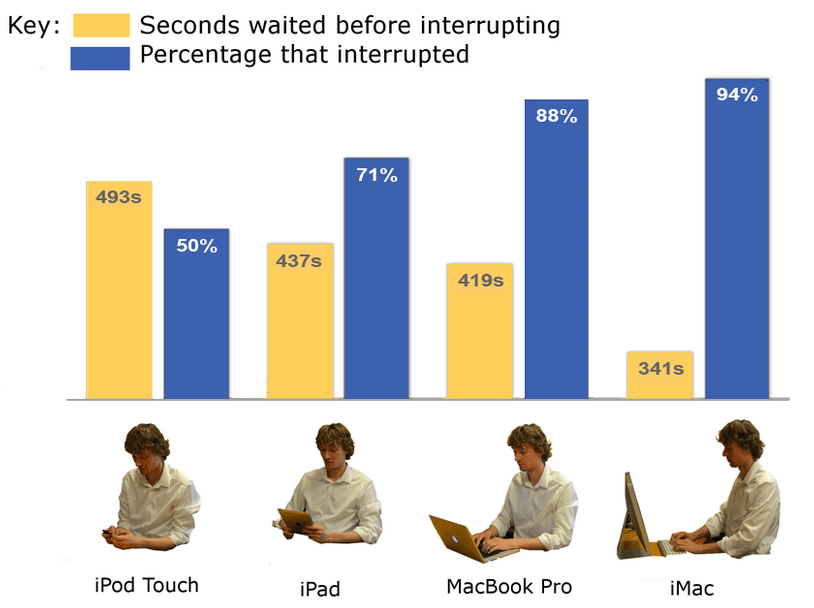

In their study entitled ‘iPosture’ they asked participants to complete a number of tasks and then wait for 5 minutes for the researcher to return. The researcher specifically told them “I will be back in five minutes to debrief you, and then pay you so that you can leave. If I am not here, please come get me at the front desk.”, and then deliberately delayed their return by up to 10 minutes. Some participants completed the tasks on an ipod Touch, others on a tablet, laptop or desktop. Cuddy and Bos found that more assertive behaviour - measured by whether participants sought out the researcher and came to the front desk - tended to be linked to the larger electronic devices used.

- Of the participants using a desktop computer, 94% took the initiative to fetch the researcher back. For those using the smallest device, the iPod Touch, only 50% left the room.

- Of those who did leave the room, the size of the device appeared to affect the amount of time they waited. The bigger the device, the shorter the wait time. Desktop users waited around 5 and a half minutes before fetching the experimenter, for instance, while iPod Touch users waited over 8 minutes on average.

Bos sees the implications of this finding in our everyday lives: “People are always interacting with their smartphones before a meeting begins, thinking of it as an efficient way to manage their time. We may, however, lose sight of the impact the device itself has on our behaviour and as a result be less effective.”.

Further work is needed in this new area of research; Bos and Cuddy are currently building on this initial study and conducting further testing – for instance on how the device we use in the workplace may impact our assertiveness and confidence.

Conclusion

We are at an end of our three part series on how online behaviour is different from offline in significant ways. Over the series we have seen how we can be more prone to use mental shortcuts and rules of thumb, how we can powerfully be swayed by the status quo and yet can also act more individualistically and more honestly. And, finally, that our very physical interaction can behaviourally prime us in powerful subconscious ways.

But let’s remind ourselves that research into behaviour in the online world is only just beginning. What is already clear is that the behavioural sciences can give us both the strategic tools to make more sense of online behaviour as well as the executional tools to influence it. The Behavioural Architects are working with many leading companies from around the world, applying frameworks and concepts from the behavioural sciences to develop and optimise online journeys and, at the same time, building on this exciting and evolving knowledge base about online behaviour.

And above all, as you think about your own online behavioural journeys and ways to optimise them, never forget that ‘It’s behaviour Jim, but not as we know it!’

So as we said in part one keep thinking, ‘It’s behaviour Jim, but not as we know it!’.

So as we said in part one keep thinking, ‘It’s behaviour Jim, but not as we know it!’.

This piece was written by Crawford Hollingworth, Liz Barker and Jamie Halliday, The Behavioural Architects www.thebearchitects.com