The potential of technology to advance healthcare with AI assisted healthcare and robotics, telemedicine and personalised medicine is the great hope. But there is also strong evidence from the behavioural sciences that tiny changes, with minimal costs, can also have a big impact on improving our quality of care. And let’s be honest, we need every tool in the box to help our current fragile healthcare system.

This article is the ninth in our ‘BE 360’ series on how behavioural economics is increasingly being applied in the world around us to nudge and steer our behaviour. We’ve covered a wide range of different sectors - from finance, to living healthier lifestyles, charitable giving, and citizenship. This article continues that theme, but takes a step back from consumer - or citizen-facing - nudges and looks at how people - patients in this case - are getting better outcomes through the application of BE to guide and improve the decision-making of doctors and healthcare workers, ensuring more accurate diagnoses, safer and lower cost treatments and more transparent decision-making.

We all know that doctors and clinicians suffer huge burdens on their decision-making. In an ideal world, they would have unlimited time, boundless cognitive energy and resources which they could use to collate all relevant information regarding each patient in order to make a diagnosis or treatment decision. They would be able to draw on multiple resources such as scans and screening, as well as basic monitoring to assess patients, before finally applying cognitive energy to process the information, perhaps making some statistical calculations along the way, to reach a final decision. With all that precision and care, they’d be reasonably confident that the decision they ultimately made would be the right one.

![]()

We all know the ‘ideal world’ scenario is unrealistic.

Clearly, healthcare workers don’t live in the ideal world, they live in the real world. And it’s one in which they are often stretched for time, short staffed, short of beds, short of resources and restricted by budgetary constraints, always trying to keep the costs down.

In addition, they are also often tired and stressed by their heavy workload and decisions are made under extreme pressure.

However, there is convincing evidence from the behavioural sciences that diagnoses and treatment decisions made using systematic mental shortcuts and evidence-based rules of thumb can perform just as well and, more often than not, better than more complex processes. Research by behavioural scientists such as Gerd Gigerenzer have shown that more information does not always lead to the most accurate answer. Rather, application of a rule of thumb approach, using simple and transparent processes which ask only a few sequential yes/no questions and rely on a few key pieces of information can be far more accurate. These processes are known as Fast-and-Frugal decision trees.

Improving diagnoses and treatment decisions using Fast and Frugal decision trees

Behavioural economists Julian Marewski and Gerd Gigerenzer tell the tale of Professor Complexicus and Doctor Heuristicus:

- Professor Complexicus is known for his scrutiny - he takes all information about a patient into account, including the most minute details. His philosophy is that all information is potentially relevant, and that considering as much information as possible benefits his decisions.

- Doctor Heuristicus, in contrast, relies only on a few pieces of information, perhaps those that she deems to be the most relevant ones.

Who do you think is the more effective physician? You might assume that it’s Professor Complexicus due to his thoroughness. Yet you’d be wrong. In test after test, in a wide range of diagnoses and treatment decisions, from diagnosing heart failure, treating children with pneumonia, HIV testing, cancer screening or diagnosing depression, less is more.

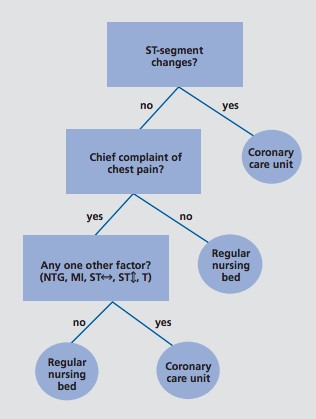

Take this fast-and-frugal decision tree developed and tested by Lee Green and David Mehr at the University of Michigan Medical School.

In a rural hospital in Michigan, doctors were sending 90% of patients complaining of severe chest pain to the coronary care unit (CCU) with a suspected heart attack, preferring to err on the safe side in a climate of litigation. Yet this diagnosis was leading to too many false positives; the actual proportion of patients who had suffered heart attacks was only 25%.

Not only was this overdiagnosis expensive, but it was also leading to an overcrowded coronary care unit, reducing the quality of care for those who really had a heart attack and putting the patients who did not need to be there at risk of hospital infections. Not to mention instilling unnecessary panic amongst numerous patients and their families.

They designed a simple fast-and-frugal decision-tree where doctors only needed to ask three crucial questions (see diagram right).

The first question looks for anomalies on the patient’s electrocardiogram. If anomalies are found, patients are sent straight to the CCU. If not, a second question asks if the patient’s primary complaint is chest pain and a final question checks if five other factors are present.

They compared their simple decision-tree with an existing, more complex decision-tool; the Heart Disease Predictive Instrument (HDPI) where doctors need to check for the presence, absence and combination of seven symptoms and match findings to a chart containing around 50 probabilities and then calculate a logistic regression using a calculator to determine if a patient should be admitted…. Sounds complicated doesn’t it?! No surprise then that many doctors didn’t like using it. But how accurate was it compared to Green and Mehr’s decision-tree?

The simple decision-tree was more accurate. 95% of diagnoses were correct compared to only 70-80% using the more complex HDPI tool. Moreover, doctors also preferred using it; it’s easy to remember and simple to apply, and, significantly, it was better suited to the time-stretched, cognitively demanding context in which they worked.

Improving patient care by changing the default treatment

Another trial drawing on behavioural science has also succeeded in improving cardiac patient care.

The Nudge Unit at Penn Medicine Center, University of Pennsylvania, increased rates of referral for cardiac rehabilitation (known to reduce mortality by as much as 30% in high-risk patients) from 15% to over 80% simply by making referral the default for all patients.

Qualitative research in the form of interviews with cardiologists revealed that the existing referral process was manual, so they had to take action to initiate the referrals, opting patients in. Redesigning the process as an opt-out system led to far better treatment and quality of care for patients whilst retaining freedom for clinicians to opt out of the default if they did not think rehabilitation was necessary.

Reducing costs by making generics the default prescription

Healthcare institutions are continually striving to balance quality of patient care with cost efficiency. One clear area of cost saving comes from the prescription of generic drugs - chemically identical to the branded or proprietary versions, just as effective and yet usually a fraction of the price. Given that doctors write hundreds of prescriptions each week from a wide range of treatment drugs, these costs can quickly add up.

In the NHS, generic prescribing has been rising since 1976 and stood at 84% in 2015. The Kings Fund estimates this has saved the NHS around £7.1 billion in total. However, they calculate there is still room for improvement, with potential for rates to rise to 90%, especially as there is variation between general practices. In the US, generics prescription rates stand at 89% on average but again, could be higher. In a society where the payment often falls on the patient, generics use plays an even more important role since patients are nearly three times more likely to abandon a branded medication because of the high cost.

To encourage more generics prescription, Mitesh Patel, Director of The Nudge Unit at Penn Medicine Center recently trialled a tiny tweak to the prescription order system on the University of Pennsylvania Electronic Health Record system. When doctors there select the drug they want to prescribe they click on a drop down menu. Previously, branded drugs were listed at the top of that menu and generics at the bottom. Patel flipped the order so that generic drugs were listed first. It had an astounding effect. Before the trial, the generics prescribing rate at Penn Medicine was around 75.0%. Immediately after the change in the drop down order, the generic prescribing rate increased rapidly to 98.4% and remained there for the ten-month test period.

Why might this tiny change have had such a big impact?

Sometimes the order in which items are listed can have subconscious effects on our decision-making.

For instance, it may be that doctors presumed the medical community’s preferred choice of drug was the one listed first. Or perhaps, short of time and energy, they scrolled down to the first drug they saw that matched what they were looking for and looked no further.

Patel comments “...it required only a minor modification to the order entry system. It took very little effort, but will probably save millions of dollars over the next few years for patients, insurers and the health system.” Whilst he admits that one of the biggest barriers to these kinds of interventions is that many clinicians are resistant to change and the concept of being ‘nudged’, he counters that “we often don't realize that we are already being nudged by the design and choice architecture of whatever electronic health record system we are using. It influences our choices every day, but often this is overlooked."

Conclusion

The examples provide a snapshot of just a few of the simple, low-cost, yet astoundingly effective initiatives leveraging behavioural science to improve patient care by improving clinician decision-making. Moreover, we may soon see more units like the Penn Nudge Unit, currently one of its kind, working to integrate behavioural science into medical processes and IT systems. Whilst AI-assisted healthcare is taking the limelight, BE-assisted healthcare may be equally deserving of some attention!

How BE is transforming our lives 24/7 series - article 6

Behavioural economics (BE) is still a buzzword in many sectors, even after breaking into mainstream thinking several years ago and making a significant difference to our everyday lives.

In something of a salute to this, we are running a series of articles over the next 12 months to take our readers on a 360 degree tour of how behavioural science is transforming our lives 24/7; how it is shaping better outcomes for us, enhancing communications, increasing our engagement and response rates and making us healthier and better off.

Each part of the series will zoom in on a particular area or sector.

Sources

- http://www.information-age.com/digital-diagnosis-ai-crucial-role-nhs-123470199/; https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/06/3-ways-ai-and-robotics-will-transform-healthcare/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3341653/pdf/DialoguesClinNeurosci-14-77.pdf

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9300001

- http://thegovlab.org/nudge-units-to-improve-the-delivery-of-health-care/; and http://nudgeunit.upenn.edu/projects/using-default-options-increase-referral-cardiac-rehabilitation

- https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/blog/2015/07/how-much-has-generic-prescribing-and-dispensing-saved-nhs

- https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/blog/2017-generic-drug-access-and-savings-us-report

- The Penn Nudge Unit was launched in 2016, to systematically develop and test approaches drawing in behavioural science to improve health care delivery and is the world's first research unit of its kind established inside a health system.

- http://nudgeunit.upenn.edu/projects/using-default-options-increase-generic-medication-prescribing-rates

- https://ldi.upenn.edu/news/nejm-spotlights-penns-history-making-nudge-unit