Around four billion people, almost two-thirds of the world’s population, experience severe water scarcity for at least one month of the year, and half a billion live with constant water scarcity. In fact, since 2012, the World Economic Forum has put water supply crises among its top three global risks in terms of impact, putting it on a parwith weapons of mass destruction, climate change and the outbreak of infectious disease.

The problem is not looking like it will abate: The UN forecast in 2014 that two thirds of the world’s population will be living in water stressed areas by 2025. By 2050, demand for water will increase by around 55%, driven by a 60% global increase in food demand, together with a 400% increase in demand for water for manufacturing in developed countries. The World Bank also forecasts that water availability in cities could fall by as much as two thirds by 2050, as a result of climate change and competition from energy generation and agriculture.

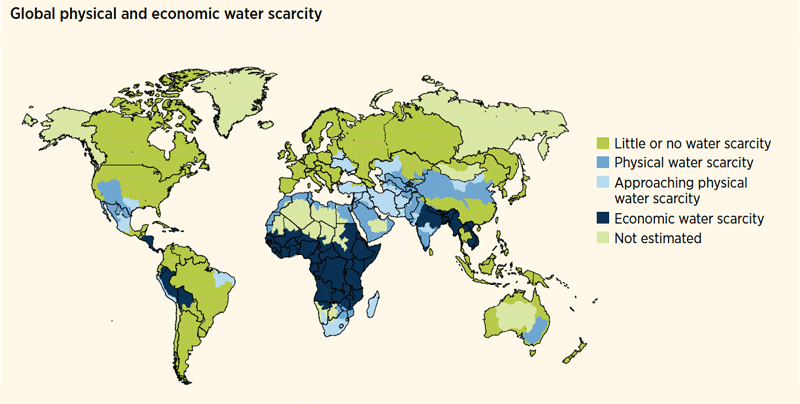

Most affected currently are households, industries and farmers in Mexico, the western US, northern and southern Africa, southern Europe, the Middle East, India, China, and Australia, where already they regularly experience water shortages.

Recently, Cape Town only narrowly averted ‘day zero’ - the day when taps would be turned off for its millions of residents, forcing them to queue at military-guarded standpipes for a bare minimum ration of 25 litres per day - by intricate and cautious management of its supplies. But other regions face long-term risk too.

So whilst a significant proportion of the current water supply is used by agriculture, we individuals and households still need to take on some of the burden and manage our water more carefully. And it has inspired a number of organisations to develop and test innovative approaches to get households using less water.

UN World Water Development Report, 2012

What might be preventing us from cutting our water usage?

Research, both qualitative and quantitative, by these organisations, have identified several barriers preventing households from better managing water:

- A major one is that we use it habitually, often without really being aware of the actions that trigger us to use it. We turn on the taps, run the shower and flush the toilet on autopilot, without consciously being aware of it. Research by Michelle Lute, Shahzeen Attari and Steven Sherman found that 80% of people feel flushing the toilet is something they do habitually, driven by having been taught to do so at a young age.

- Secondly, utilities companies don’t make it easy for people to understand their water usage, with no clear reference points (known as anchors by behavioural scientists) and consequently customers have a poor understanding of how much water they use. Water bills are typically reported in cubic metres. Yet research in Costa Rica by Ideas42 and the World Bank found that people find it hard to visualise cubic metres of water and lacked intuition into whether an amount billed was large or small.

- Billing is also fairly infrequent, meaning that there are large time lags in feedback. Timely feedback on an activity or task can help to motivate us, increasing our engagement and ultimately, helping us achieve our goal. So behaviour is often more malleable when we receive real time feedback, rather than months after the event often because it allows us to change our behaviour immediately without any delay.

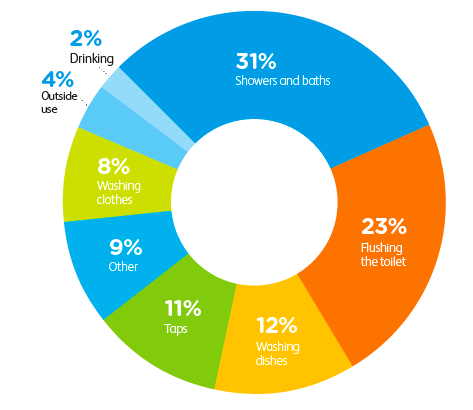

- Also, because the bill comes as a lump sum, it’s hard to understand what changes in water usage might have the most valuable effects and people often struggle to outline specific steps they would take to reduce their water usage, not even believing it could be reduced significantly. Some people mistakenly believe that changes such as turning off the tap whilst brushing their teeth will make a difference. Whilst every little effort helps, it’s actually showering, bathing and flushing the toilet that use the bulk of our water (see diagram).

- Another barrier is the relatively low cost of water compared to other bills, meaning that any potential savings often don’t feel worth the effort and more like pocket money, especially for more affluent households. People anchor or compare their relatively small water bill to the bigger bills such as electricity and conclude that potential savings on their water bill are negligible. Research by ETH Zurich found that households are often not responsive to price increases because water is relatively cheap and seen as a necessity.

- Finally, we also often misperceive others’ water use. It’s easy to notice outdoor water-heavy activities such as neighbours washing their cars or watering their garden, but we may be less aware of others’ indoor water use. Since we are often guided by what are known as social norms - by what we see others doing - we may feel ‘licensed’ to continue using water as we always have - an ‘if no-one else is making an effort why should I change’ attitude.

Given these problems and barriers to change, what steps can be taken to help people to reduce their water consumption?

Saving in the shower

A major large scale study run by ETH Zurich has found that providing people with real-time behavioural feedback on how much water they are using relative to the ideal might be one solution. First piloted in Switzerland in 2012, this approach has now been trialled in the Netherlands, Germany, South Korea and Singapore with considerable success. This trial targeted shower use only, recognising that showering accounts for more than 80% of hot water demand and a good chunk of overall water demand. Behavioural scientists have also learnt that specific goals are often easier for people to work towards than broader ones. Since people are often unsure what action exactly to take to save water, focusing on a single objective could likely lead to bigger impacts.

Almost 700 households received smart shower meters, which could be easily installed on a handheld shower at eye level in the shower and requires no battery, simply being powered by the water flow.

The meter displayed how much water and energy had been used since the shower had been turned on together - giving people instant and salient usage feedback which behavioural scientists have found effective in motivating people to change behaviour. As they watch the litres used rising, they might be motivated to stop singing and hurry their shower along.

The meter display also showed an ingenious animation of a polar bear on an ice flow. If someone took a very long shower, the ice flow began to shrink and melt and eventually the entire animation disappeared! This initiative really made salient the connection between high energy consumption (to heat the water), carbon footprint and climate change.

Anyone watching the ice flow start to shrink might be more motivated to hurry and turn the taps off.

One group were also given the same information on their previous shower as a reference point. Another group also received feedback on their energy efficiency rating. All this information helped to give feedback at the right time for people to take action. Verena Tiefenbeck who helped run the study says: “We provided the information in real time so that people saw that feedback as they took their showers, while they could still do something about it.”

The impact over the 2-month trial was significant: people cut their shower time by around 20% on average, reducing water consumption by 21%.

This also cut energy consumption by 22%, resulting in yearly savings of 452 kWh for a 2-person household or roughly 12-13% of the average European household’s electricity bill. To put that in perspective, a fridge freezer uses around 427 kWh per year and a plasma TV 658 kWh. A previous study by ETH Zurich testing the impact of electricity smart meters found only an 86 kWh reduction - five times less than the shower study and showing that a narrower focus can reap more gains than broader targeting. The device was also pretty inexpensive, paying for itself within 9 months from savings on water and electricity bills. Whilst the initial pilot ran for only 2 months, later studies have typically run for 3-6 months and found no drop off in impact. The meters have also been installed in 9 Swiss hotels and have also received a positive response with the savings almost as big as those in households.

A similar study run in Singapore for 16 months found the same level of impact. Whilst the shower meters still gave real time feedback, the intervention differed slightly in that households were given varying water conservation targets of 10, 15, 20, 25 or 35 litres. They found the most effective target was 15 litres - a moderate volume target - where people used 3.9 litres less water an average. A 10 litre target was less effective, with people on saving 2.9 litres, probably because it was too ambitious - 10 litres is really not a lot of water! 20 litres or more was just too easily attainable for people so they did not have to make much effort to adhere to it.

A simple nudge to reduce water usage

Other organisations have had success with even simpler initiatives, simply changing the communications received from water companies to nudge reductions in water consumption. In 2014, ideas42 and the World Bank partnered for a project in Belen, Costa Rica is already being affected by periodic water shortages yet general awareness campaigns run by the municipal authorities and raising rates by 70% had not had an impact.

Qualitative research had revealed that providing people with comparative points of reference may help to influence their water usage as well as helping people better understand what behaviours could help to reduce their water consumption.

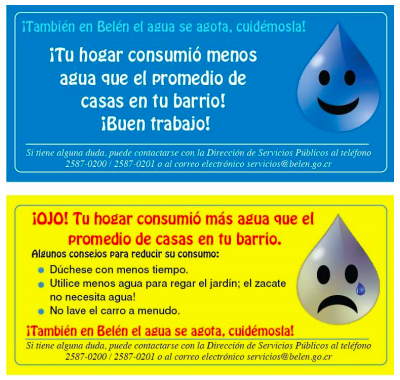

So, one solution was developing stickers (see examples) to go onto bills informing households about how their usage compared to either their neighbourhood (group 1) or the city (group 2). One had a happy face to congratulate a household with consumption below the median and a second had a sad face if usage was above. From a behavioural science point of view, we know that people generally want to fit in and conform with what others are doing, following social norms, so knowing that we are using more water than others around us could be enough to prompt us to take action.

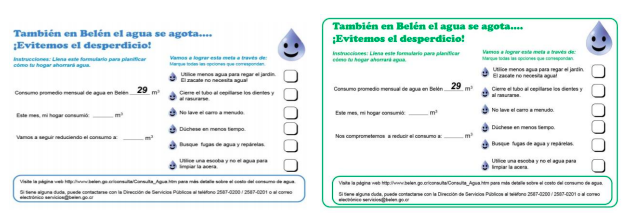

A second initiative was to send out postcards (see image) to all households showing average monthly consumption in the area, providing households with a much needed reference point - known as an anchor in behavioural science - to compare their own usage to;

- A space to record their own usage;

- A space to set a target to reduce their consumption for the month ahead (group 3). Setting a specific target can make us feel more committed to achieving that goal. Writing it down (especially in public) can escalate this even further;

- 6 specific ways to save water, such as using less water in the garden, showering for less time, fixing leaky pipes and sweeping the sidewalk rather than hosing it down. Identifying concrete steps to take to meet a goal or target can make it feel easier to achieve.

Overall, there were 5,600 households involved in the trial, split into the three test groups plus a control group who received none of the initiatives. By analysing households’ water usage over the next 2 months and comparing it to average consumption rates for those months in the previous year, the research team were able to deduce if any of the tests had had any impact.

The neighbourhood stickers worked; households receiving those typically cut their water consumption by between 3.7% and 5.6%. The postcard also helped too with reductions between 3.4% and 5.6%. (The citywide stickers did have an impact too, but a smaller one.) This was a relatively low-cost solution amounting to just $400 worth of stickers - a valuable approach for low income or developing countries who may not have resource for technology based or more complex solutions.

In summary

Water is our most precious resource but often our most misused one and one we take for granted. Cape Town earlier this year is just another wake up call for all of us. In this article behavioural science helps us understand why we might often behave in a profligate manner with water - from our tendency to discount the future, our deeply embedded habits and also the fact that energy don’t communicate our usage in the most cognitively easy ways. The examples we discuss here, which aim to counter our profligate behavior, have shown us that by leveraging behavioural science in simple ways - with minimal expense - such as leveraging real time feedback, social norms or giving us simple reference points, we can have a radical impacts on our water consumption habits.

So, go on, turn that tap off.

How BE is transforming our lives 24/7 series - article 10

Behavioural economics (BE) is still a buzzword in many sectors, even after breaking into mainstream thinking several years ago and making a significant difference to our everyday lives.

In something of a salute to this, we are running a series of articles over the next 12 months to take our readers on a 360 degree tour of how behavioural science is transforming our lives 24/7; how it is shaping better outcomes for us, enhancing communications, increasing our engagement and response rates and making us healthier and better off.

Each part of the series will zoom in on a particular area or sector.

Sources

- World Finance, The threat of water scarcity looms large, Oct 2017; https://www.worldfinance.com/news/the-threat-of-water-scarcity-looms

- http://www.un.org/waterforlifedecade/scarcity.shtml

- UN World Water Development Report 2017 http://www.unesco.org/new/en/natural-sciences/environment/water/wwap/wwdr/2017-wastewater-the-untapped-resource/

- WEF Global Risks Report 2017; World Bank. 2016. High and Dry: Climate Change, Water, and the Economy. Washington, DC: World Bank;

- FT, South Africa: How Cape Town beat the drought, May 2018 https://www.ft.com/content/b9bac89a-4a49-11e8-8ee8-cae73aab7ccb

- Don’t rush to flush’ https://static1.squarespace.com/static/54e39dcfe4b033c7e0e77c20/t/557f279fe4b0aba21c85408a/1434396575815/DontRushtoFlush2015.pdf

- http://www.toolsofchange.com/en/case-studies/detail/697/

- Based on the European household consumption average of 3600 kWh. UK households typically consume slightly more than this - 3800 kWh. Source: Gov.uk and Ovo

- https://www.straitstimes.com/opinion/targets-real-time-feedback-can-cut-water-use-in-the-shower

- http://www.ideas42.org/blog/project/encouraging-water-conservation/ and http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/809801468001190306/pdf/WPS7283.pdf