We tend to give what others have given before us

We are wired to copy others and to follow societal norms, especially when we’re unsure what to do, short on time, or feel pressure to conform and ‘fit in’. From choosing a restaurant based on the simple fact that it’s busy, to buying the same insurance policy, car or gadgets as our friends and family, we are driven to ‘fit in’ and do what others are doing. Might that apply to charitable donations too?

We are wired to copy others and to follow societal norms, especially when we’re unsure what to do, short on time, or feel pressure to conform and ‘fit in’. From choosing a restaurant based on the simple fact that it’s busy, to buying the same insurance policy, car or gadgets as our friends and family, we are driven to ‘fit in’ and do what others are doing. Might that apply to charitable donations too?

To test this idea, researchers conducted an experiment over the course of 2 months at a free art gallery in Wellington, New Zealand. They placed a transparent donation box in a visible location in the entrance lobby of the gallery and then varied how much money it contained.

The contents of the box varied during the study in that the box was either filled with NZ$100 in a variety of denominations:

- Mostly coins, (made up of lots of 50 cents!);

- Small bills, ($5 x 20);

- Large bills, ($50 x 2); or

- Contained no money at all.

Over the two months the gallery had around 21,000 visitors. Tracking contributions by visitors revealed that donation amounts tended to reflect the original contents of the box. New visitors tended to copy what other visitors had given before them. For example, a donation box containing a large quantity of coins resulted in a large number of small, coin-based contributions, whilst a box containing a few larger denomination bills resulted in a smaller number of contributions, but at a higher value.

Boxes with money inside attracted significantly higher donations than completely empty boxes.

This illustrates how social norms can sometimes influence when and how much we are likely to give. Seeing that others have already made a contribution seems to make us more likely to give, since we want to conform with what others have done before us. The coins and bills in the box may also serve as an anchor or reference point to suggest what amount may be socially appropriate to donate. Amounts and denomination might also signal the wealth or generosity of previous donors. Seeing the box is full of coins might signal that even the least well-off donate to this cause, whereas a box with a couple of $50 bills might signal that only the well-off or particularly generous or devoted art fans donate.

We tend to give what the last person gave

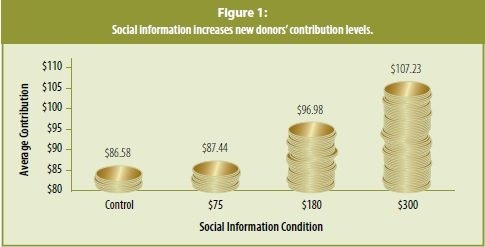

Another study found a similar effect. Mentioning the size of the previous donor’s contribution also seems to increase donation amounts.

Rachel Croson, an economist at the University of Dallas, and Jen Shang, a psychologist at Indiana University, examined data from a phone-based public radio station pledge and observed how knowing how much previous donors had given could encourage listeners to make larger contributions.

When callers were informed that a previous donor had made a contribution of $300 (where the average contribution was $75 dollars), they gave an average of 12% more.

We might explain this by reasoning that, as in the previous experiment, we want to conform to what others have given. But behavioural scientists also note that we tend to make decisions by anchoring to reference points. In this case, the previous donor acts as the reference point and people adjust their own donation based on that amount. Note that if the contribution mentioned was too large, people did not give more, illustrating, as a previous study by Leif Nelson and colleagues also found, that anchoring effects have their limits. If the reference point we are given is too high, we pay no attention to it.

Making a caller aware of a similarity between them and the previous donor raised giving even higher. One group of callers was told, “We had another donor who gave $300”. A second group of donors was given similar information, but with the previous donor’s gender matched to the caller’s: “We had another donor; he/she gave $300.” Sharing the same-gender as a fellow donor resulted in a 34% increase in donations, compared to the more general benchmark. Whilst we often want to conform to what others do, we are even more likely to conform if the ‘others’ are like us – and we have something we value in common with them.

Charities could benefit from making prospective donors aware of what others have already given. Some donation platforms, such as JustGiving (see image) provide an option to make this visible, but more likely we are just given a selection of donation amounts to choose from.

We tend to give more when reminded of our previous donations

Behavioural scientists and psychologists have found that we like to be consistent in our actions and maintain our identity.

This seems to be true for many types of behaviour – from being a voter, giving blood, to playing sport and other leisure activities. If we’ve voted before, we feel compelled to vote again, if we’ve given blood in the past, we feel compelled to give blood again. A team of behavioural scientists set out to explore whether reminding people of their past donation(s) to a cause can increase the likelihood they will donate again to the same cause and even donate more.

This seems to be true for many types of behaviour – from being a voter, giving blood, to playing sport and other leisure activities. If we’ve voted before, we feel compelled to vote again, if we’ve given blood in the past, we feel compelled to give blood again. A team of behavioural scientists set out to explore whether reminding people of their past donation(s) to a cause can increase the likelihood they will donate again to the same cause and even donate more.

In a large-scale field experiment conducted with the American Red Cross (ARC), researchers sent direct mail to over 17,000 individuals who had previously donated to the ARC but had not contributed in the last 24 months. All letters used the greeting, “Dear Friend and Supporter,” but one set of letters also included the note, “Previous Gift: [date]” below the postal address.

Researchers found that including this extra line increased the probability of a donation from 6.3% in the control group, to 7.6% - a 20% increase. Importantly, average donation amounts also increased by around 4%, from $3.41 in the control condition to $3.83 in the ‘Previous gift’ group. Whilst the increase in amount donated sounds small, if the entire mailing had included the extra line, the ARC would have raised an additional $7000; that’s $65,000 instead of less than $58,000.

Reminding donors of their identity as supporters of the ARC also played a role in nudging people to feel the need to maintain that identity by donating again, and even donating slightly more. People want to be seen to be consistent with past behaviour; society generally frowns upon inconsistent behaviour such as changing opinions and actions, or not following through on commitments.

Those who have been past donors often feel greater commitment to give again.

So charities could make good use of this finding by highlighting people’s previous donations and forging their identity as donors. If we have donated before, we are more likely to donate again – especially if we are reminded of it.

We might give more when we can signal to others we are donors

Yiwei Zhang, Judd Kessler and Katy Milkman at the University of Pennsylvania recently looked at what might prompt alumni to give to the university. One hypothesis they tested was whether someone receiving recognition as a past donor in the university’s Honour Roll might prompt them to give again and/or give more. The society we live in approves of loyalty, and consistent giving to good causes is an excellent example of this. Add to this our desire to be known to be conforming to these social norms. Zhang and her team wondered if alumni might value the opportunity to signal their loyalty.

Taking a group of 120,000 Penn alumni, they introduced two public recognition programs for alumni who gave to the University in consecutive years. One program publicly recognised any donor in an Honour Roll, ranking them by $ brackets so that not only would others see that they had donated, but they would also get a rough idea of how much. A second program tagged donors with a symbol after their name on the Honour Roll if they had given consecutively over the last three years, allowing donors to signal they were frequent and consistent donors.

In the year the programs were introduced, those eligible for recognition were significantly more likely to donate and donated more relative to those who were ineligible.

The first program raised donations – some people even gave just enough to qualify for the next bracket up! In the second program, alumni were attracted to the symbol after their name and the prospect of being publicly recognised for previous sustained donations dramatically increased donations in the current year.

Both programs, however, leveraged our desire to show society we are altruistic people. (And perhaps, more cynically, allowed people to show fellow alumni they were making enough money to donate regularly, boosting their status.) Charities and fundraisers could capitalise on this insight by publishing names according to the amount donated or ranking their most consistent and regular donors.

A better future

We are not only altruistic, but we are also social creatures, and recognising this can help us to become an even more giving society.

These simple insights from the wealth of research produced by behavioural scientists today – that we are more generous when we are more aware of what others have given, when we are reminded of previous donations we have made to the same cause and if we are able to signal to others that we are a generous or regular donor - could be applied to help us build a better, even more altruistic society.

How BE is transforming our lives 24/7 series - article 3

Behavioural economics (BE) is still a buzzword in many sectors, even after breaking into mainstream thinking several years ago and making a significant difference to our everyday lives.

In something of a salute to this, we are running a series of articles over the next 12 months to take our readers on a 360 degree tour of how behavioural science is transforming our lives 24/7; how it is shaping better outcomes for us, enhancing communications, increasing our engagement and response rates and making us healthier and better off.

Each part of the series will zoom in on a particular area or sector.

Sources:

Charities Aid Foundation, UK Giving Report 2017

Martin, R. and Randal, J. “How is donation behaviour affected by the donations of others?” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 67 (2008) 228–238

Shang, J. and Croson, R. “A Field Experiment in Charitable Contribution: The Impact of Social Information on the Voluntary Provision of Public Goods” The Economic Journal, 23 June 2009; and Non Profit Quarterly, Social influences in giving, Croson and Shang, 21st Sept 2010, https://nonprofitquarterly.org/2010/09/21/social-influences-in-giving/

Kessler, J. and Milkman, K. “Identity in charitable giving” Management Science, December 16, 2016